Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I have done something really fun with today’s Dividend Cafe – at least fun for me. I have taken the most common questions I receive these days from clients, in emails, in meetings, in interviews, etc., and compiled a set of answers that walk through the big issues of today. I think you will find it valuable.

I doubt I cover everything on your mind here, so by all means fire away with new questions. You may just see it covered in The DC Today, and you will certainly hear from me personally.

In the meantime, let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe.

|

Subscribe on |

Have equities become cheap?

God no. No, no, no. Are they cheaper than they were a year ago? Sure. Forward multiples were 24x and are now more like 19x. Backward multiples were a preposterous 32x and are now more like 20x. So p/e ratios for S&P index investors were high, and are high, but yes, they are not quite as high as they were.

As you will see in my next section, bonds have become a more interesting investment option, which creates more competition for stocks across the board (and puts downward pressure on valuations based on the rising risk-free rate).

But that is not to say that equities are a bad idea. It is to say that indexing is a sub-optimal way to be exposed to equities. Indexing requires mass-market valuation expansion, and it certainly suffers from mass-market valuation compression. I would argue that there is a good chance of more of the latter, and almost no chance for the former, for some time ahead.

Equity returns where the focus is on growing earnings, cash flows, and dividends are a different subject than returns focused on multiple expansion. This should be a huge theme for risk-takers for years to come.

What is your updated view on owning bonds?

A huge thesis in our use of “Boring Bonds” out of the COVID moment was that two of the three benefits of the asset class for nearly a hundred years had done away. The idea in high-grade bonds, treasuries, high-quality munis, etc. was always that:

(a) You got a decent interest income

(b) You had principal preservation

(c) You had a hedge against “tail risk” if really bad things happened.

My view was that A and C had gone away in the world of ZIRP, and that only B remained. By the grace of God, that has changed in the last six months, with some form of coupon (still well below historical averages) back on the table, and me now having every expectation that if something dramatic happened to the stock market or in a geopolitical/news/headline event, yields would collapse and bonds rally.

Yet the primary benefit still remains letter B above – that “safety” component of a portfolio that one wants just to have out of the domain of risk assets. For many investors that allocation should be 0%. For others, it should be hefty. Goals and psychology matter here. I use my allocation to boring bonds merely as dry powder for the ability to add into equities in a tail risk event, and it is a small % allocation.

But the fact of the matter is that boring bonds are exponentially more attractive now than they were two years ago, and the negative performance in the asset class these last 6 months is exactly the reason why.

What should the ideal interest rate be?

This is, of course, an impossible question to answer because in a perfect world prices would be discovered, not imposed, and the Fed would have no role in setting the price of money (markets are perfectly capable of doing so without an intervening hand). And to be honest, the 10-year bond yield is not set by the Fed, but it is more influenced by central bank interventions than it should be.

As the great Charles Gave says, “the market rate should be as close as possible to the natural rate.” This is not a controversial assertion, but it always begs the question of what the natural rate is or ought to be. I am sympathetic to Gave’s view that the natural rate ought to equal the long-term growth rate of corporate profits, which is essentially what the long-term growth rate of the economy ought to be. Now, one may point out that the relationship between the growth of GDP and the growth is corporate profits is hardly linear, and that is true, but that is because of “noise” – and ultimately, if you understand what real WEALTH CREATION is – that is – ECONOMIC GROWTH (GDP), you will see that it must be identical to CORPORATE PROFITS and that in fact, this is a tautology. Indeed, can someone tell me how wealth is EVER created aside from profits? Have fun with that one.

So, if the natural rate is equal to profit growth, I want the 10-year bond yield to be in line with such because when the rate dips below that natural rate it encourages leverage, financial engineering, and gamesmanship. And when it gets above the natural rate it obviously encourages excessive debt paydown, low capital expenditures, and pulverizes growth in a deflationary cycle.

So that is my general rule of thumb – a 10-year bond yield in line with profit growth. But if the question is what the fed funds rate ought to be, I can only say it has become far, far, far too important of a measure in our economy and as a mere overnight rate it is subject to so much noise and intervention as to be worthless as a real economic indicator, and instead is used as a manipulative policy tool that is doing more harm than good in its present utility.

Do you still think that the current inflation is not primarily about Biden’s spending bill?

That the fiscal spending of 2021 was not the primary cause of 2021/2022 price inflation is most evidenced by the fact that the fiscal spending of 2001-2020 was not inflationary, that the fiscal spending of Europe as debt-to-GDP has blown out was not inflationary, and that the fiscal spending of Japan for 30 years has not been inflationary. In other words, the burden of proof would be on those countering 30 years of empirical counterfactuals, not those looking at perfectly plausible explanations for this year of price escalation data.

But nevertheless, further empirical support for the position that excessive and reckless fiscal spending is inherently DEFLATIONARY cannot hurt, lest we be caught shell-shocked when long-term stagnation resumes. And I mention these two things to provide further support for a more coherent explanation of current inflation.

Inflation is not at a 40-year high for the U.S. only; it is at a 40-year high for virtually all countries. What do all these countries have in common? It isn’t blowout debt-to-GDP over the last two years. That explosion of fiscal spending (debt-financed) is our unique claim, with dozens of countries experiencing the same inflation growth with nowhere near the same fiscal spending growth. No, what the other countries have in common is the need for food and energy.

So did those two things experience inflation merely because of excess spending driving huge demand growth? Demand in 2019 was 99.7 million barrels of oil per day. It is 99.4 per day now. Yes, we are 9 million barrels per day higher in demand now than we were in 2020 COVID, but we are basically back to even (not quite even that) in terms of pre-COVID demand. So why price inflation in oil if demand is merely the same as it was in 2019? Answer: Supply.

We can do the same exercise with Food. People are not hungrier now than pre-COVID. There are ghastly supply issues that have caused significant price escalations – globally.

When it comes to other elements of goods and services, there are price escalations in the U.S. that trump the food and energy story. But my point is that the Food and Energy story provides a far better Occam’s razor to the global inflation story than the mere fiscal spending explanation, which I will argue does WORSE damage than inflationary damage over time – and that is, it puts downward pressure on future economic growth.

Both of these things can be true at once:

- The Biden effort to limit supply in the energy sector and the consequences of the 2021 Biden spending bill in the labor market (i.e., huge labor shortages) have massively contributed to inflation.

- The real damage of excessive 2020 Trump spending and 2021 Biden spending will be long-term suffocation of growth, not inflation.

Are we going into a recession?

In a word, probably. Is it assured? No. Is the timing knowable? No. Is the depth and magnitude predictable? No. But is there a ~50% chance of a recession in 2023/24? Sure. That sounds right and unhelpful.

As I have written before, recessions are misunderstood and misapplied in portfolio management. The underlying thought is that the tightening financial conditions we face as the Fed undoes what they have done will force a contraction of economic activity that becomes recessionary. It is common and likely but not assured. The main thing I would add to the subject – the tightening the Fed now has to do calling into question the exit of COVID monetary policy is not merely the unwinding of COVID era decisions, but in fact, a long-overdue reality of the post-GFC monetary regime (i.e., great financial crisis). We have been in a 14-year monetary experiment, and there is no way to know how this plays out.

I am not merely saying that I don’t know or that you don’t know. I am saying that they don’t know.

What is the Fed thinking right now?

The Fed knows that the one thing the public has less tolerance for than price inflation is a recession. Current price levels are a regressive tax on low-wage earners, and the public is mad, but the current angst pales in comparison to a real recession, and a real surge in unemployment. The Fed believes that the need and demand for labor right now is so much greater than its supply that even with tighter money and less aggregate demand there will not be a surge in unemployment. Maybe. But I will tell you this from the bottom of my heart: They don’t know, and if they start to fear it is going the other way, they will panic.

Job openings are high – that is the accurate data point on which the Fed is relying. But widening credit spreads and other economic conditions will be watched closely. I am sure the Fed is getting the fed funds rate higher than I previously thought they would. But hiking the rate until inflation reads 2%? I would not take that bet.

What would be the best thing for the economy right now?

A rise in productivity, period point-blank. What would cause this? Increased capital expenditures combined with more workers coming back to the labor market. This would generate more efficiency and more productivity and would create a supply-side resolution to both inflation and excess liquidity.

Am I predicting this? No. Am I praying for it? Daily. Sometimes hourly.

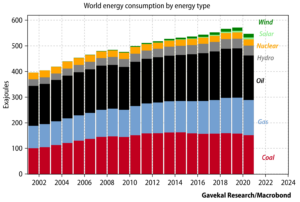

Chart of the Week

Energy consumption is on the rise, now in 2022 back to 2019 levels (nearly), and about to tick higher when China re-opens. It would seem fossil supply remains important in this consumption reality.

Quote of the Week

“Necessity is the mother of invention”

~ Plato

*I don’t think he ever really said this. But he said something similar, and we have run with it for a long time now.

* * *

I do understand it has been a wild ride in the markets. I understand some may feel nervous. I also understand that the strong performance of the energy sector and the dividend growth world has largely offset anxieties within the Bahnsen Group client roster. But that can change, too. It is a vulnerable time, made all the more vulnerable by the various experiments being played out in real-time.

So we will keep writing, reading, talking, explaining, answering, and most of all, caring. To that end we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet