Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I did something fun today … I just picked random topics from various things on my mind, in my daily reading, or across my research feed – sort of stream of consciousness – and wrote about them. Therefore, I suspect there will be a little something for everyone today. Hopefully, each portion is “bite-sized” enough to make it all succinct and readable, and I certainly appreciate any feedback you have to offer. In fact, I am considering something like this in the daily DC Today (where I would write my own piece every day on whatever topic I am so inspired by that day and let Brian run with the daily data recap). It’s all a work in progress, and your comments are welcome.

And in the meantime, let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe – bite-sized variety and all …

|

Subscribe on |

QT for me but not for thee

Why do I believe the Fed will face a reckoning moment regarding quantitative tightening at some point? Last year, the removal of supply from the financial system was offset by the fact that (a) Budget deficits were large, leading to huge new issuance of Treasuries, and (b) There was ample appetite to buy that supply in the market because rates were high. Money could leave the banking system (money supply dropped a lot) even though Treasuries were soaked up the market. This year, policy objectives are leaning the other way. They will want lower rates, which makes Treasury appetite in the private sector lower; all the while, budget deficits should be somewhat lower, leading to a marginally lower new supply. Quantitative tightening at the same tight would be a mixed/contrary policy objective, and ultimately I believe the Fed will be asked to pick.

Green shoots of optimism for the objective

One of the things I am more and more convinced we have seen in the economy of 2023 and 2024 is what we would have seen without the COVID interruption of 2020-2022 – and that is, some health in the economy in the aftermath of the post-GFC era. From deregulation to enhanced business investment to reduced corporate income taxes to greater hiring at higher wages to some modest improvement in business optimism, the 2017-2019 era got interrupted by a timeout in normalcy 2020-2022.

A desire to paint the 2017-2019 years as not productive to the economic base because of who was President then is somewhat dishonest, just as it is to deny the position of the economy in 2023-2024 because of who the President is.

A China explanation

The 2023 projection that China’s COVID re-opening would be a big catalyst to economic activity, not only domestically but globally, proved to be way off, as was covered at great length in my annual recap. It has still begged the question as to why it was that China did not experience the same economic bounce that we did, let alone Europe, Canada, Australia, and others.

The always insightful Louis Gave has posited a theory I am pretty sympathetic to. Essentially, during COVID shutdowns, western governments paid workers to stay home and not work (or barely work), and when we re-opened, a good-sized minority did not go back to work, pushing up wages due to a shortage of workers (all pretty indisputable facts so far). As Louie’s thesis goes, this wage increase boosted demand quickly in the U.S., whereas in China, wages dropped when they re-opened because migrant workers flooded back to the previously closed centers of economic activity. Furthermore, this happened in concert with ongoing distress in their construction sector, all working together to put downward pressure on demand in the immediate aftermath of the COVID re-opening.

As explanations go, this one has a lot of sense to it.

A growth story in China

There is one sector where China is not in contraction, where exports are rising, where market share is jumping, and where not only is the U.S. buying but other foreign countries are, heavily, and where their domestic base is on fire … Electric vehicles. Even Elon Musk has said the greatest (and, according to him, only) threat to Tesla from EV competitors is in China …

And yet, the EV sector in China has been crushed. Rising sales. Rising exports. Rising market share. Declining stock prices. Batteries that become obsolete. A lack of parking spaces with chargers. Shipping costs that erode margins.

Sometimes, an investible thesis requires more than just the shiny part.

Politics brought to my crystal ball

Do you want to know the only prediction I feel safe making after the 2024 election is over as far as the impact on the economy and markets?

With no prediction at all about who will win the White House or Congress (the Senate is obviously more likely, but never assured, to flip to the GOP), here is my prediction:

Deficits are not coming down. Spending is not coming down. Austerity is not on the horizon. Easy monetary policy will be needed to accompany easing fiscal policy.

A non-emerging view on China

Most emerging markets were very China-heavy for the last twenty years and remain so now (though less so than has been the case much of the last decade). We have never been China-heavy in our limited EM exposure, but that is sort of beside the point right now.

Why are U.S. investors (and other global players) steering clear now? Is it the fear of what the CCP might do next (things like CEOs that go dark for months at a time or policy regulations that come out of nowhere, which literally put massive companies out of business)? Is it economic analysis that calls into question China’s economic strength? Is it geopolitical risk (Taiwan, Russia friendliness, U.S. adversity, etc.)? Or is it just a limited opportunity set combined with a landscape that makes it very trendy not to own Chinese equities? My answer to all these questions: Yes.

Who you calling risk-free?

A key principle in investment finance is the concept of a risk-free asset – a sort of benchmark or universal default product that any asset can be measured against. A risk-free asset provides a proper comparable when evaluating any given potential investment because all of economics deals with trade-offs, and basically, the risk-free asset enables us to ask these questions: “What is the return I would be getting versus the return I could get anyways?” – and “what level of risk do I have to take, versus the option of no risk?” Once that baseline is set, then opportunities and costs can be properly measured.

I have always believed that some form of short-term treasury bill is the optimal risk-free asset. If the term is short enough (say, 90 days), there is not really duration risk – that is, the concern of price volatility as interest rates go up or down. There is not default risk, as the bonds are backed by the full faith and credit of the United States government. And for U.S. investors, the T-bill being dollar-denominated means there is not really currency risk (you buy with dollars and receive dollars back – no exchange of other currency involved).

There are some who use a long-dated treasury bond in the way they think about a risk-free asset, and I certainly understand that comparables of longer-dated bonds (say a high yield corporate bond) to a longer-dated treasury bond make sense. If, for example, a 10-year treasury paid 5% and a pretty junky corporate bond paid 5%, it would be very easy to say, “This risky bond doesn’t make sense when I can get the same return with no credit risk and the same duration risk elsewhere.” So the spreads versus longer-dated bonds matter, but that doesn’t make the longer-dated treasury the optimal “universal risk-free asset” – there is still duration risk, but also policy and currency risk. A lot can be done in ten years to intervene (monetarily) with the value of the currency underlying the bond, and certainly, a lot can be done with interest rates to alter the function of the bond. I believe the yield of a 10-year government bond ought to equal the nominal GDP growth of the economy over that time (inflation plus growth), and so monetary policy that seeks to put that rate below or above such a natural rate is distortive and ruinous to the risk-free function.

But can’t they do it in 90 days, too, you ask? Well sure. I guess I would just respond by saying, “It’s easier to do over ten years than 90 days.” So it is relative.

But it all leads to one very important conclusion at the heart of how I view monetary economics, which is to say, the role of money, time, credit, and interest in all of economics: Distortions from a central bank of the price of money might seem to create a certain visible economic benefit, but they can never do so without altering a less visible economic measurement – the risk-free rate. And that can truly do damage to investors in their assessment of risk and reward.

An economic lesson, continued

I read a lengthy report earlier this week from the masterful Charles Gave that inspired this important reminder. As I believe the Fed is (wisely) about to start cutting rates from their excessively high place now, yet I worry that they will end up loosening to a place that is excessively low (their favored position), I wanted to remind everyone why people like me (and Charles) find excessively low rates (those set below the structural growth of the economy) so problematic: Artificially low rates crush savings. Who wants to save when the rates are too low, and when by borrowing you can benefit from the low rates? YET, a reduction of savings means a reduction of investment (S=I) as all invested capital is first saved capital, and a reduction of investment means declining productivity.

A line that should never be uttered in markets

I hear a lot, often from “retail investors,” but with equal frequency from “professionals” and institutional investors – that the way a certain asset is performing “makes no sense.” When a certain currency, stock, market, or security is doing better than someone thinks it should, it is because “something makes no sense.”

Well, in the spirit of a little humility here, those are very stupid words. It always “makes sense.” Now, that is totally different than saying “it is sustainable” or “it is properly valued.” But behind any asset we ever believe is mispriced, there is usually one of two explanations at play, both of which “make sense” …

One is that we have gotten something wrong. It isn’t mispriced. It seems that cheap because something we don’t see is broken, or it seems that expensive because there are greater fundamentals than we comprehend.

But even in the highly frequent circumstance of genuine irrationality … That still “makes sense” – because humans are irrational, all the time. Think of the decisions people make in their personal lives that go against logic and good sense. It happens, and it happens in pricing, too (usually in temperamental and emotional moments of either fear or greed). Excess in human nature is common, so a mispriced asset always “makes sense.”

And unfortunately for some, it always “re-prices” in due time, too.

Chart of the Week

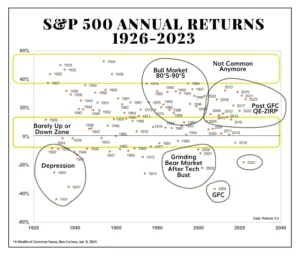

This is one of the most fascinating charts we have ever done. You see, in historical cycles, the cluster of years that were so positive in the 80’s/90’s bull market (many 15%+ years) and then that same cluster in the post-GFC era. You see, the massive 40%+ years that really don’t happen anymore. And you see those terrible drawdown moments, rare as they are, where the downside was pronounced. But it is that “barely up/down zone” that becomes interesting to me post-GFC.

Quote of the Week

“In politics, good gets better and bad gets worse.”

~ Haley Barbour

* * *

Well, have a wonderful weekend, and reach out with any questions at any time. We are one week away from a huge passion project of mine, Full-Time: Work and the Meaning of Life, coming to doorsteps. While not a markets book, per se, it does explain a little as to why I work in markets the obsessive way that I do, though hopefully, it provides a little color for how and why all of us can enjoy our vocational endeavors more.

In the meantime, to all these ends, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet