Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I had promised more of a summary this week on my takeaways from the extraordinary Mauldin Strategic Investment Conference, and indeed, this week’s Dividend Cafe forced me to deal with several issues that were front and center at the conference – the dollar, oil, interest rates – to name a few. I think you will find this week’s Dividend Cafe to be filled with topics and ruminations that were inspired or provoked by the conference, and I hope you will find my ruminations to be half as interesting as I found the conference to be.

So much of being an investment manager comes down to formulating your broad view of markets and the world, and then implementing a framework for investing that is compatible with that broad view. I can personally assure you that a substantial amount of the professional investor class (a) Has no view of markets and the world, and (b) Has made no effort to implement a framework for investing that matches some macro view of the world. One day I will decide if “no view” is preferable to “the wrong view,” but I have been undecided on that for years. I think deep down I prefer the wrong view because I find “no view” so intellectually lazy and professionally inadequate.

But as I said, one’s view of the world – their macro assumptions – their general beliefs about macroeconomics, geopolitics, and key drivers of growth and trends in the years and decades to come – is not the end of the story. If one takes the time to formulate presuppositions and beliefs, they then have to develop a framework for implementation and execution. Money is not managed in a vacuum. There are real-life people with real-life goals and situations that require the optimal application of a given set of views.

I have obsessed over the macro view of things (what I call in certain contexts, “first things” or “first principles”) for a long, long time. I have done so as it pertains to economics and finance since I was blessed to enter this field, but even that stemmed from an upbringing where my late father forced me to approach all of life that way. It was actually Socrates who told us to do the critical thinking necessary to formulate foundational ideas – to ask probing questions until we had formed “first principles.” But it was my dad who taught me that those foundational ideas were inescapable, and carried with them a responsibility to be applied correctly.

I am constantly challenging myself to get my applications of “first things” right in the investment world, but my principles themselves are not constantly changing. I say that with pride. The challenge that exists for the investment professional who has done the work of developing operative principles is to constantly evaluate their application of said principles, to alter, change, adjust, or modify as needed. And here is the other piece to that: To thoughtfully consider what it would mean to their client’s capital if they were wrong. Investing client funds as if one can not be wrong in investment application/execution/implementation is the height of arrogance. The humility to constantly check one’s work and one’s strategic thinking is a money-saving character trait. Sometimes it gets forced upon you in my business.

So this week’s Dividend Cafe focuses on many first principles in investing, and many beliefs we have about executing on our principles. But it also hopefully reflects the humility that is needed in risk management.

Principles. Conviction. Humility. To these ends, we work.

Let’s dive into the Dividend Cafe.

Three Key “Things”

One of my favorite sessions in the Mauldin Strategic Investment Conference last week was economist, Louie Gave (of Gavekal Research, which I read religiously every single day) suggesting that there are three major categories in which significant consensus has been formed by investors and that within these three major categories there is application risk should these views be wrong.

(1) U.S. dollar – have all investors formed a view that the dollar is going up/up/up, and this will not change? On the outskirts of this discussion, is the dollar’s upward trajectory not only in question but even its long term status as the world’s reserve currency?

(2) Oil – have all investors formed a view that oil is going down/down/down, or at least staying low/low/low?

(3) Interest rates – and have all investors formed a view that there will be downward pressure on rates as far as the eyes can see? And what if inflation pressures surprise us, and long-term rates move higher?

Three Thoughts about these Three Things

Dollar first: I do believe there is too much belief that the dollar cannot adjust downward, and I do believe it is vulnerable to an adjustment. I also believe there would be little resistance to such as the “defenders of the dollar” no longer see themselves in that role. A weaker dollar is the policy aspiration of many, and I am quite confident that both the White House and the Fed would take a weaker dollar if they thought they could create one. The problem is not that the U.S. is doing too much to make its currency look attractive – it is that another currency has to relatively step up and take its place, and that is easier said than done. There are real and absolute reasons to question King Dollar, but when you apply those reasons to Yen, Euro, and Renminbi, you do not walk away feeling resolved. I am highly skeptical of those who question the dollar’s long-term reserve currency status, and I say that more because of “everything else” than I do the dollar itself.

Oil: I am not sure if there really is a consensus view that oil will stay low forever, but I am sure that if there is, it is wrong. Supply/demand rules apply to autocracies and small-cap shale companies alike, and a supply/demand balance in oil prices will come post-COVID. I would not formulate a view of inflation, consumption habits, or geopolitics that assumes $25-$35 oil forever. I would not assume it for another six months, to be honest.

Interest rates: This one I need to spend some time with because I am most certainly in the camp that believes we face downward pressure on interest rates for the foreseeable future. This downward pressure will be both organic (there is inadequate demand for credit) and manipulated (the power and will of the central bank to make it so). Both the organic and manipulated forces stem from the same unchangeable reality – excessive government indebtedness.

Dividend Selectivity

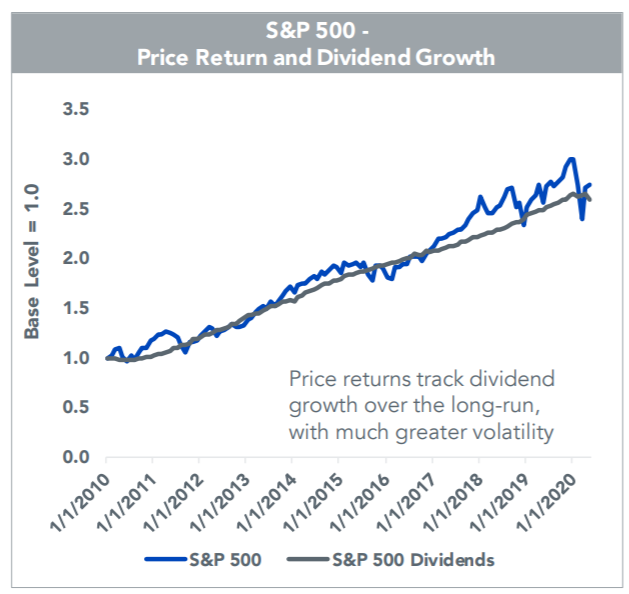

Can the concept of dividend growth (which serves as the cornerstone of our investment philosophy) be obtained passively, as many equity investors have been programmed to pursue in recent years? There is no question that the S&P 500 has enjoyed robust dividend growth over the years, having paid out $18 in 1974 (the year I was born), and $58 last year,

But never mind what the dividend level represents in yield (less than 2%), and the substantial amount of companies in the index that pay no dividend at all, it is dividend cuts that are the great enemy of a dividend growth strategy. And the S&P 500 is now expecting a 14% decline in dividends paid in 2020. In fact, they saw a 25% decline in 2008.

Now, there are very good reasons for this. This is not a criticism of the companies in the index who are cutting the dividends or the S&P for having those companies in the index. It is only a criticism if the investor believed the approach was immune from dividend cuts. The index construction is making no effort at all or claiming to make any such effort, to avoid dividend cuts. In fact, in the 46 years, I have been alive, one-third of them have seen the S&P pay out less in dividends than it did the year before.

Now, that could lead one to say, “okay, the S&P is not a good passive way to get dividend growth, but what about a passive index that does focus on dividend growth?” And yes, there are some. Many (most?) have yields less than that of the S&P 500, meaning the criteria of a robust, superlative starting yield is not important to them, but more importantly, they wait until a company has cut the dividend to remove it from the index (if then), and make no efforts to actively monitor the propensity and ability of companies to continue paying the dividend. (In fairness, “no effort” is sort of the point of being “passive”).

Dividend growth matters for income investors, and it matters for accumulators. And if all investors had a better understanding of investment finance, they would see that it matters to everyone. After all, even for an index bad at capturing consistent, year over year growth – the volatile prices ultimately track – you guessed it – the dividends.

* Wisdom Tree, Dividend Monitor, May 21, 2020, p. 2

Reflation Reality

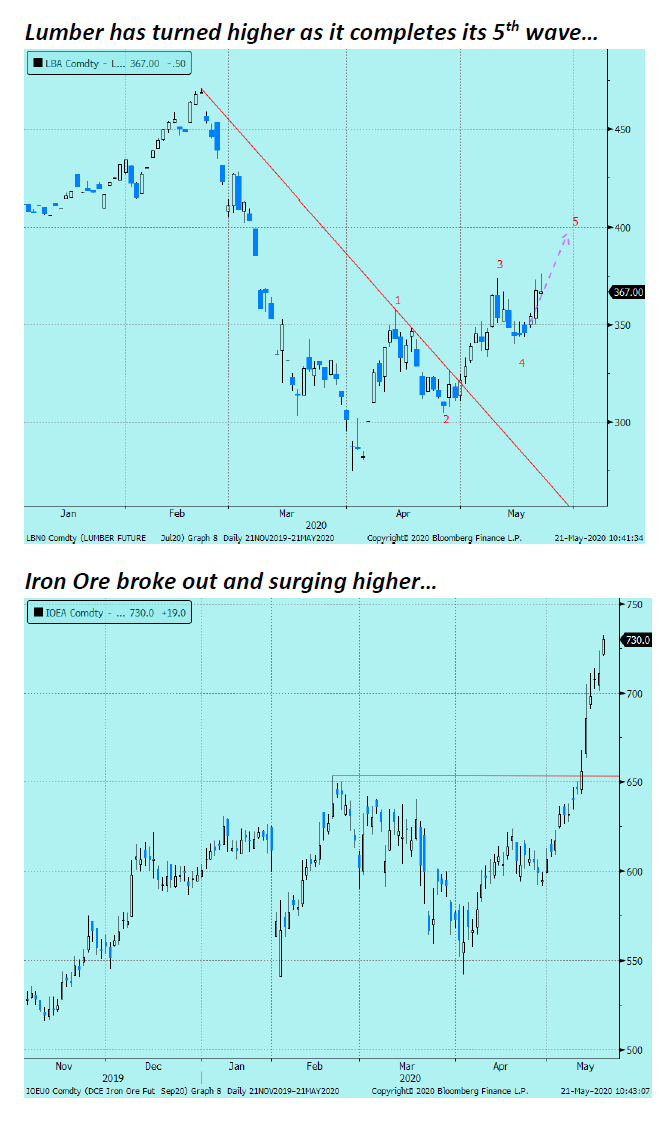

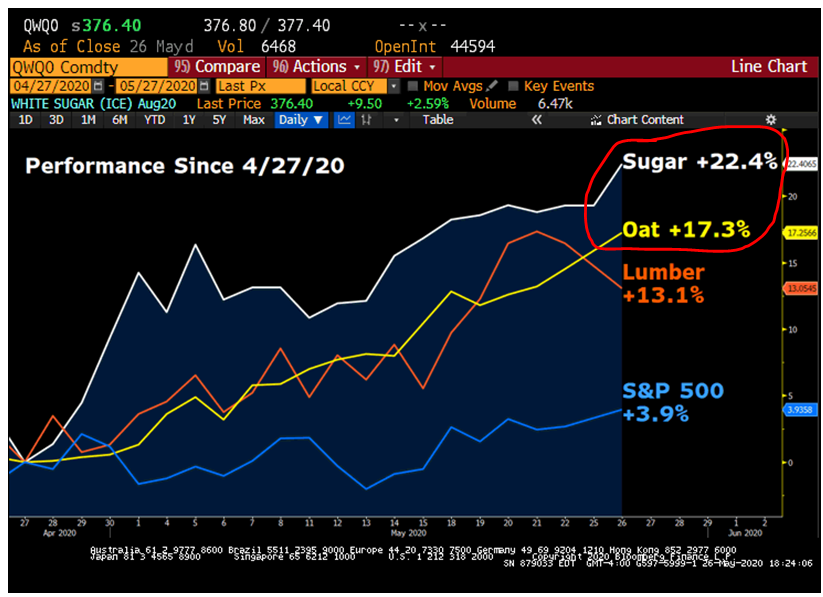

The rebound of crude oil off of its brutal lows, I have argued, has been a story of supply and demand expectations – namely, that supply gluts were changed to production cuts, and demand evaporation moved into some demand resumption (albeit, not enough, yet). If there were not confirmation from other commodity prices it would be entirely possible that the oil story had no normative application – that it was idiosyncratic to the unique events of OPEC, geopolitics, and shale that often color the oil price story.

However, I would argue that we are indeed in a reflationary moment, whereby diminished supply levels from the shutdown of production and reignited demand (at some level) from the gradual re-openings point to a better growth environment for the economy. Lumber, iron ore, copper, agriculture, food, etc. confirming the story of crude oil provide necessary but not sufficient to the present reflation thesis. It’s on our radar.

* Macro Scan, Prism Financial Products, Mark Orsley, May 21, 2020

Agricultural commodities are now joining in the rally as well, with the Agriculture Commodity Index up 17% in May. The reflation trade of which I speak has not just been limited to hard commodities relative to construction but food commodities (and obviously energy) as well.

A Decade-Long Viewpoint on the Oil & Gas Story

As a believer in the American energy renaissance story, and an investor in what has been the “golden age” of that story (2009-2014), as well as the “bear market” of that story (2015-2016), it behooves me to have a viewpoint on the future of the story, and not merely the past. Investors in the upstream aspect of oil and gas (exploration, production, services) experienced extraordinary returns from 1990-2005, and investors in the midstream aspect (transportation and storage) experienced extraordinary returns from 2009-2014. There have been lackluster returns across all aspects of the industry’s verticals since 2016, with up and down movements coming out of (a) Commodity price volatility, (b) Challenges to the financial models, and (c) The cost of Capex/infrastructure investment. Demand growth, however, did not hold back the energy sector – these other extrinsic forces did.

The challenge now is not to merely evaluate the transitory zigs and zags around demand levels this quarter or inventory levels next quarter, but to formulate a more holistic viewpoint on:

(1) The future of the industry’s cost curves

(2) The [new?] capital structure of the industry

(3) Supply/demand realities of crude oil and natural gas (including liquefied natural gas)

The first two points provide a lot of context as to how the U.S. shale industry has survived 2015-2020. The marginal cost of production is not low enough to survive all sorts of secular demand contractions, but it came down so dramatically from 2009 to 2015, and since 2015, that it did change the understanding of the rules. And the manner in which companies financed their operations was long-term unsustainable (but short-term survivable), and now has experienced a sizable transformation in the last two years.

Our view is that the upstream cost curve is likely to stay flat. More consolidation will happen, and exploitation of cost synergies around that consolidation could drive break-even prices down by as much as $10/barrel. This improved dynamic for the upstream players leads to more stability in the midstream, where counterparty risk has always been the biggest concern. Couple an improved cost curve for the producers with smarter and more sustainable capital structures, and the midstream sector becomes far more attractive in the next ten years.

Scale and operational efficiency are going to be key as the investible parts of this sector move from the headwinds of supply/demand volatility and capital structure vulnerability, to a sustainable model that is more insulated from these headwinds of the last decade. Whether it is restructurings or liquidations, some of the “weaker players” in the upstream space are going away, and the industry itself will be left with companies that can operate more efficiently and with a better scale.

We do not want to re-focus our strategy on some quick-buck M&A opportunity or a levered play on commodity reflation (both of which are probably investible ideas, by the way). Rather, our view is for a sustainable and healthy business model, that captures the energy consumption needs of a world not anywhere near ridding itself of the need for oil and gas. All things being equal, we’d prefer to be invested in the natural gas (and LNG) side of this equation, as we see the cleaner solution of gas vs. coal being a theme that has staying power, and significant peripheral economic opportunities (export, natural gas liquids, etc.).

Market Redux

Markets have moved higher out of optimism in the re-opening of the economy (as phased and gradual and segmented as it has been). They have moved higher behind the extraordinary liquidity provided via monetary stimulus (M2 money supply is +31% annualized since the Fed interventions began). Markets believe (and I suspect they are tragically right about this) that the pain of the COVID lockdowns will be more felt in small businesses than large-cap public equities. Markets have moved up (and I suspect they are gloriously right about this – I certainly hope so) in the expectation that a vaccine is coming sooner than later. And finally, markets have moved higher because investors do not see a lot of great alternatives to the U.S. equity markets – not with interest rates so low, and international markets so vulnerable.

The market could be right about all of these things, wrong about all of them, or split the difference somehow. What I am very aware of is that at this market price level there is not a huge margin for error. Goals-based investors in any risk asset have to assess the risk on both sides. What happens if the market is right on all of the above conditions, and an investor has exited stocks waiting for a correction? Can anyone really claim they know that the market is wrong on all of those conditions? And what if the market is wrong on them and equities correct, yet someone is invested to their full equity allocation? Would that price correction prove temporary or permanent? And would it have a material impact on the goals of a given investor?

My best advice is that investors fully and prudently consider their allocations to each asset class that makes up their full portfolio and have a very thorough understanding of how the allocation suits their specific goals. When that process is done right, I am firmly convinced that the cost of being out when markets advance is leaps and bounds more expensive than the cost of being in when the market corrects. But that initial pre-condition – that one’s allocation is suitable to their goals and particular situation – is the key precondition to success in this market environment.

Do not worry about whether or not the market is right to value liquidity and economic re-opening the way it does, as much as you worry about your alignment of allocation decisions to your goals and objectives. That is a conviction I can share with no wavering or trepidation.

Who is buying stocks?

Here is what we do know about this rally in equities since the late March bottom: No one seems to have believed in it. Institutional managers continue to be heavily bearish per industry surveys. Sell-side analysts have downgraded 7x more companies than they have upgraded. Retail surveys show widespread negativity. Obviously we know companies are not buying back their own stock. So who is buying stocks if everyone is supposedly so negative on them?

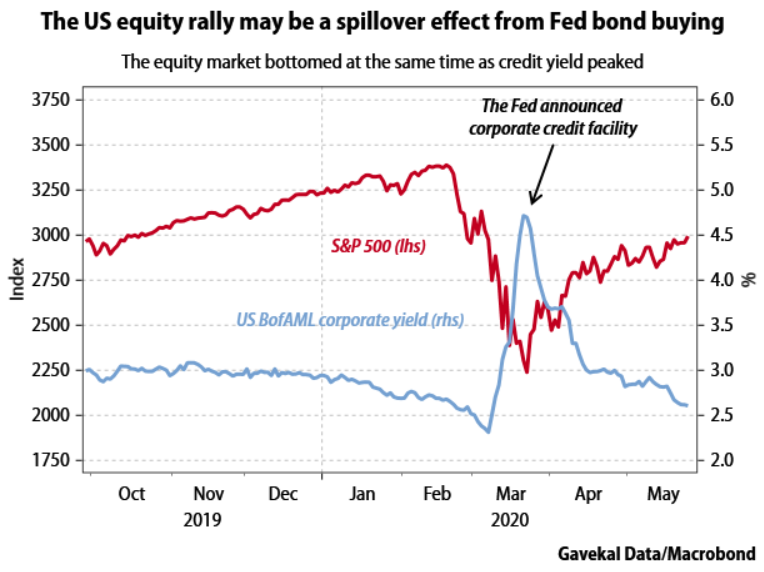

… TINA is

Our theory is that a primary driver of the equity rally, besides all the smart money folks lying about their own sentiment and actions, is the “TINA” trade – There is no alternative … The correlation between the decline in bond yields as the Fed intervened and the rally in stocks is rather evident – even if causation cannot be established.

Past, Present, Future

You can look at the chart below and see that total private credit assets moved up each year post-financial crisis, from an aggregate of $300 billion to roughly $900 billion entering this year. This is a combination of CLO’s, BDC’s, private debt, and middle-market loans. This excludes high yield and investment-grade corporate bonds, and syndicated bank loans. This is private credit growth only, post-crisis. Comments after the chart …

* Bloomberg, May 28, 2020

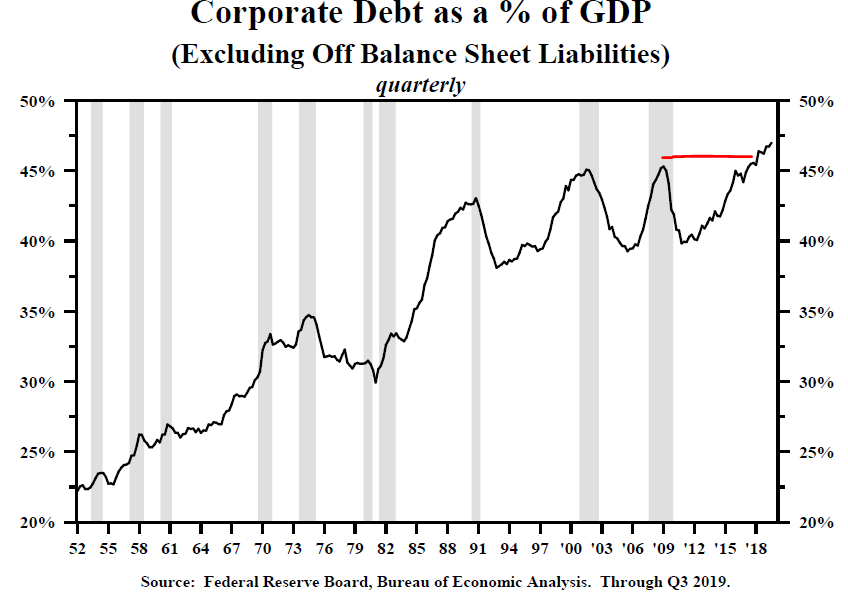

The reality is that one could look at this and say, “oh no, private markets are levering up recklessly,” but a couple of caveats are in order. First of all, it is certainly true that a good portion of this debt is debt that would still exist in a different form if it were not private credit. While bank loans and traded bonds are not for every borrower, there is no reason to believe this debt was only extended because of growth in BDC’s and CLO’s and middle-market lending innovations. Secondly, this does not speak to the productivity of the debt that is really the heart of the matter. The marginal revenue product of the debt which clearly was very high as the debt grew 217% and yet the debt as a percentage of GDP did not move past its pre-recession level until 2018.

What I am getting at here is this: We re-levered corporate America post-2008 financial crisis. We did it because the Fed was begging us to do it. And most indicators are that we did it pretty productively. But that said, a lot of debt now sits on the balance sheets of corporate America, and a lot of that debt is in private credit. The Fed’s liquidity support has been in the bond market – not private credit markets, and yet that is where a lot more of the risk has built up. The Fed is well aware of this, and candidly, the Fed helped to create it. It is both why the Fed has been supportive where they can be to credit markets thus far, and it is why I believe the future policy will factor in both the undesired risks they have helped facilitate (i.e. covenant-lite levered loans), and also the upside they want to continue (productive use of debt with low rates to spur growth).

It is a situation riddled with risk, and opportunity.

Investing in the opportunity side

We entered 2020 with a heavy theme around investing in illiquid alternatives – private equity, private credit, and other such asset classes that would benefit from less daily volatility and a more long-term process unburdened by the mechanics of daily liquidity. We did not get as much time as we would have wanted to effect some of these additions before the COVID moment, but the theme remains not just effective, but increasingly so.

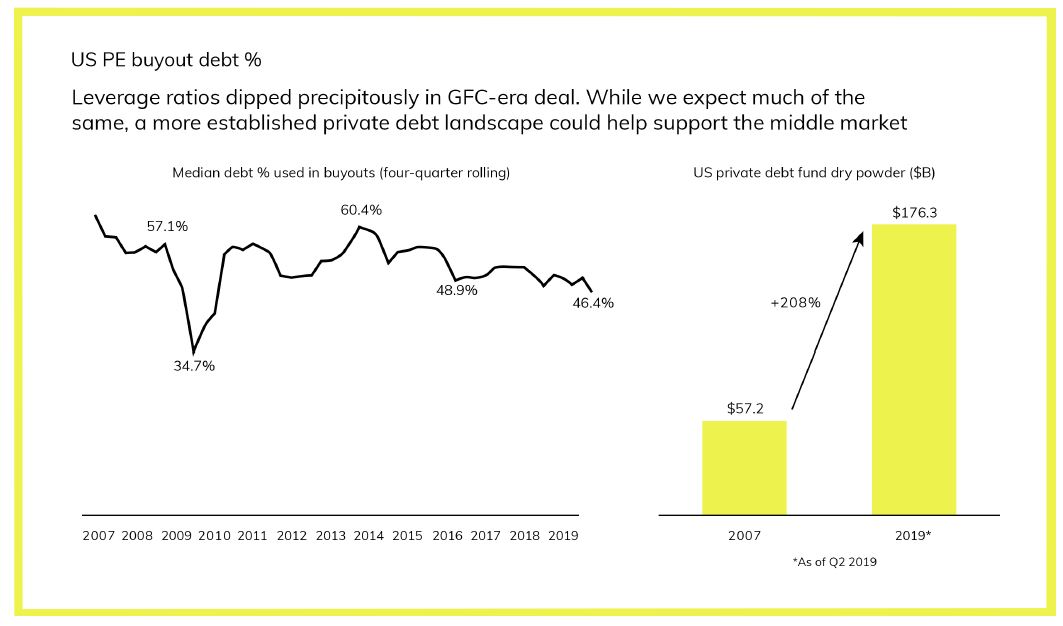

Our belief is that more opportunities now exist for private credit and that private equity deals will utilize less leverage (we like that).

* PE Hub, Q1 2020, p. 27

So you have private equity/alternative asset managers with more dry powder and more opportunity (we find this investible), and you have private credit and private equity funds that will have ample capital with which to transact, from a position of strength. The two themes we are talking about here:

(1) The dividend-paying public equity of the fee-based management companies, and

(2) The underlying private equity and private debt funds various gifted managers run and will be running out of the COVID moment

Did someone mention China?

As of press time on Friday the White House’s planned press conference to announce some new pressures on China has not happened. By the time you are reading this, the presser should have happened, and the market will have responded one way or the other. I really hate writing let alone submitting when I know there will imminently be a development that potentially renders my words obsolete, but this does contain the potential to be that short-term volatility catalyst I have been discussing.

Regardless of what happens in the interim, my forecast at this time is (all three things):

(1) Increased rhetoric against China in the weeks and months ahead

(2) Muted actions against China in the weeks and months ahead (more bark than bite pre-election)

(3) A deteriorating relationship with China post-election that will last for many years, with broad popular American support.

The Trump administration (and for that matter, the American people) do not get too fired up about the increasing pressures China is exerting on Hong Kong. It is a profoundly important issue, but not one that seems to have a lot of leverage with the American people. Rather, the key variables will be around COVID, around U.S. supply chain dependency on China (especially long term), and on compliance with the phase one trade deal (especially short term). Index fund inclusions and press conferences are not, right now, the major transformative needle-movers in this crucial and global topic. We are watching, closely.

Across the pond

The European Commission’s proposal to create a 750 billion Euro recovery fund builds on the plan from France and Germany to see debt issued by collective Europe. It is presented as a temporary emergency proposal, much as the Financial Stability Facility was “temporary” back in 2010 (hint: it’s right now bigger than ever). This isn’t scandalous; it’s par for the course (“nothing so permanent as a temporary government program”). And yet this has profound institutional ramifications, in that it expands formally the monetary union of Europe, even at a time where their fiscal union is as disjointed as ever. It doubles down on integration at a time where many see disintegration. It’s a story that may dramatically alter the generational obligations of European member countries.

Politics & Money: Beltway Bulls and Bears

- The President’s efforts this week to bring down further regulation and even structural alterations on social media companies may or may not have political ramifications. I can see it being a turn-off to his critics and many independent-minded voters who think it looks like governmental intervention in private companies, and I can see it being embraced by his base as an overdue push-back against bias and censorship. But I believe it will be more of a political and cultural moment than a market moment, as it is unlikely to alter the landscape of these company’s business models or overall societal adaptation of technology and content.

Charts of the Week

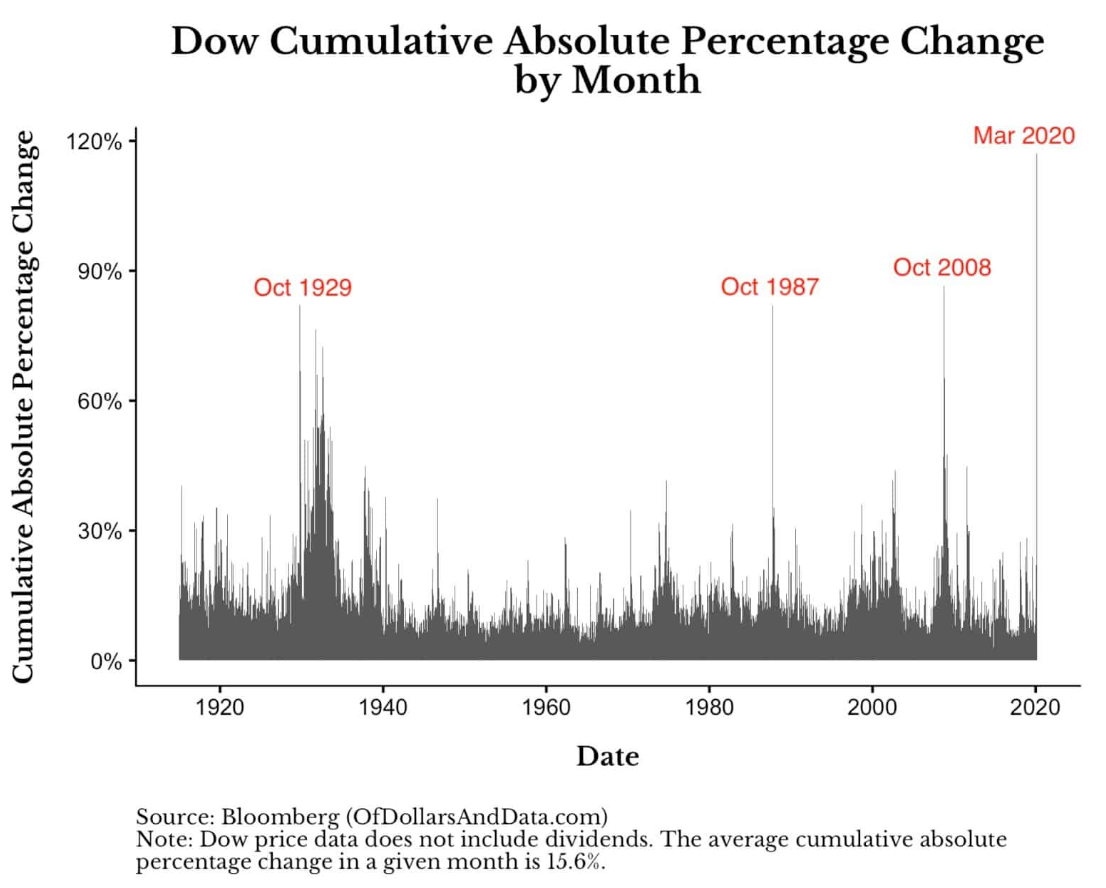

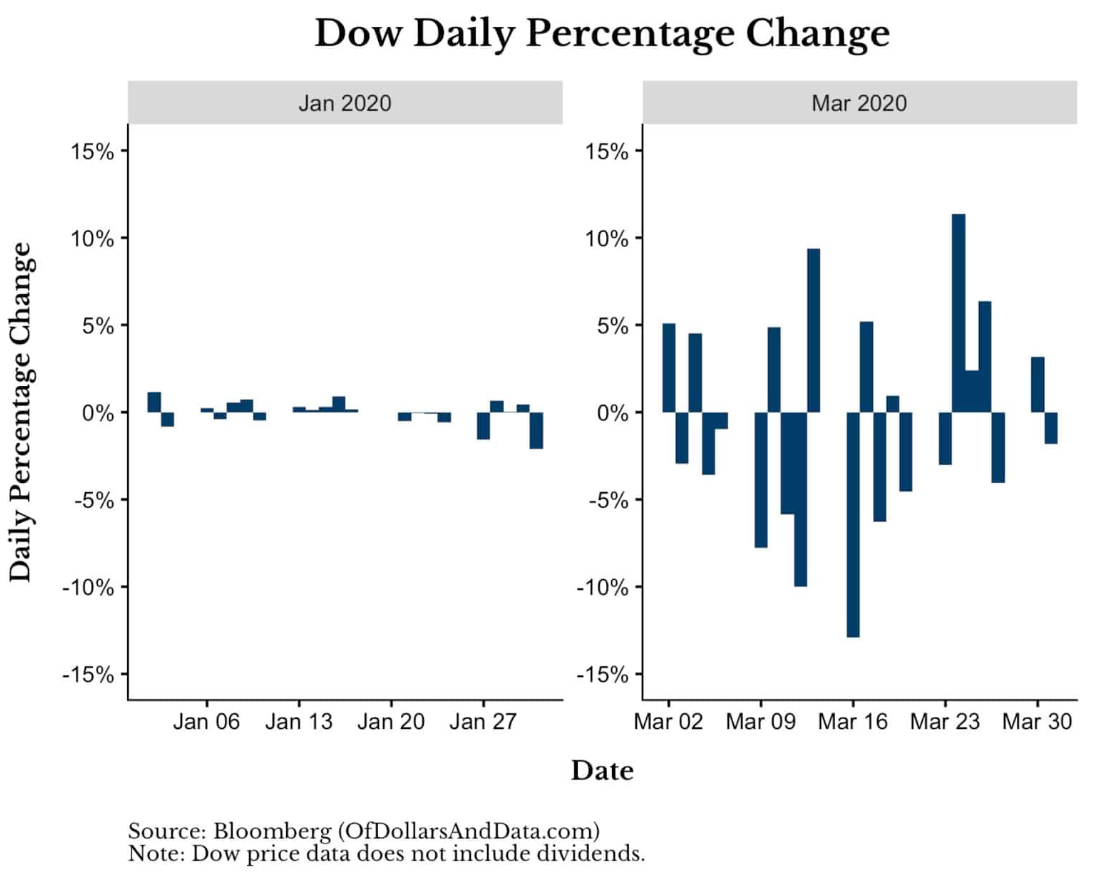

I found this to be a fascinating (and totally accurate) way of measuring practical volatility in the market. The “cumulative absolute percentage change” just simply adds up the % up move and % down move of each day into a sum total. What better captures the gravity of each daily move than that???? And by that measure, March of this year in the height of the COVID moment was the most volatile month in market history. It was not even close to the worst month in market history, but it’s sum total of up and down movements (117% in the month) made it the most volatile ever, surpassing even October 2008, the month of Black Monday 1987, and even the fateful launch of the Great Depression.

And to offer a relative comparison, note the side-by-side of a normal month (January of this year) with March. It really helps to capture what was happening in March.

Quote of the Week

“We are looking at a world with parameters bounded by pure imagination; where we go from here is anyone’s guess. Please note that we have carefully articulated the world going forward as one of pure imagination rather than suggesting we are, as some might do, looking into the abyss. We do this because we believe we are currently confronted with uncertainty; this is distinct from risk.”

~ Will Thomson and Chip Russell

* * *

Just like that, the month of May is behind us, and the traditionally sluggish months of summer are now here. Of course, this year’s summer will have a mind of its own, as surely this year’s spring has had a mind of its own.

Our thoughts and prayers are for a continued improvement in the health realities of the coronavirus in our society.

And our market focus is on good decision-making, long-term ramifications, and underlying fundamentals.

Those are both the first principles we stand behind. To all these ends we humbly work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet

The Bahnsen Group is a team of investment professionals registered with HighTower Securities, LLC, member FINRA, SIPC & HighTower Advisors, LLC a registered investment advisor with the SEC. All securities are offered through HighTower Securities, LLC and advisory services are offered through HighTower Advisors, LLC.

This is not an offer to buy or sell securities. No investment process is free of risk and there is no guarantee that the investment process described herein will be profitable. Investors may lose all of their investments. Past performance is not indicative of current or future performance and is not a guarantee.

This document was created for informational purposes only; the opinions expressed are solely those of the author, and do not represent those of HighTower Advisors, LLC or any of its affiliates.