Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

We have had a lot to say about housing here in the Dividend Cafe over the years, most recently here with a broad update of projections for supply, demand, and pricing, and more philosophically, last year’s bulletin here that aimed to provide a bigger picture perspective on how to think about it all. I was and am proud of both issues of the Dividend Cafe and the message embedded therein. Housing is a big part of the U.S. economy, where we live is a big part of our lives, and what it costs us is a big part of our monthly pocketbook.

Yet today’s Dividend Cafe is a little different. Not only am I not offering a forecast today as to whether or not median home prices will drop -9% from here or go up +5% or some other irrelevant nonsense, but I also am not speaking to some macroeconomic ramifications of housing the way many pundits do (this many construction jobs will be added or lost, or this increase or decrease will take place in spending at the Home Depots and Lowes of our economy, blah blah blah). I do happen to think most of those discussion items are silly, misguided, and misunderstood, but that is not why I am ignoring them today. Besides them being bad questions and impossible to answer, I also have a different focus that is more important to our lives and well-being.

Today I want to dig into the single biggest reality of housing that no one seems interested in talking about – and that is the cultural implications of how we have re-framed our view of residential real estate over the years. Some may prefer a discussion to the latest projections around the rocket science that is “home flipping,” but I believe our angle today is the lowest-hanging fruit of how we ought to think about this subject. Let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

The American Dream

Over the years, the notion of home ownership slipped into the lexicon of American life as synonymous with the American dream. Some form of (a) Owning a home, (b) Having economic freedom, and (c) One day retiring … became a three-part recipe for the American dream. I am as big of a fan of “morning in America” as anyone could be, yet I have always felt that productive activities were the essence of the American dream, not the things we bought from our productive activities. In other words, if a tooth fairy could just give every man, woman, and child a house (and many believe in just this sort of thing), I wouldn’t consider that the American dream. Connected to home ownership in a more intelligent romanticizing of the concept is supposed to be the value of community, a sense of belonging, and a sense of thrift, discipline, and enterprise that is actually the sine qua non of the whole thing!

I have a book coming out at the beginning of 2024 arguing that our understanding of retirement is deeply flawed, as well. By focusing so heavily on “that day when you do not have to work anymore,” we have made the point of work to, well, one day not work. It is sort of weird if you ask me.

Whether it be a more ontological understanding of work, purpose, and the American dream, our construction of these things applied to housing is incomplete at best and deeply flawed at worst.

A Noble Goal

This is not to bemoan home ownership. I have argued time and time again that owning a home and one day being free from a payment connected to that living is a matter of great financial freedom. Those of greater means who can afford multiple homes may very well increase their standard of living by doing so. When one establishes roots in a particular home in a particular neighborhood, they are far more likely to be active participants in civil society, contributing to the life of the community via the church, bowling leagues, volunteer organizations, sports and recreation clubs, social gatherings, and all sorts of the things that add quality and depth to our lives.

Everyone needs a place to live, and for those who can do so under the right financial circumstances, I am a big fan of owning the place one lives in. It adds to the freedom and flexibility of the experience and may even offer some economic benefit over time, not the least of which is eventually being free from a monthly ownership cost (or at least minimizing it to a large degree – a mortgage can be paid off while insurance, maintenance, and taxes are likely a permanent cost of ownership).

I have a more robust view of the American dream than equating it to simply owning a residential asset. I would define it more colorfully as engaging in those productive activities that marry our passions to our skills, freely practicing our religious beliefs, and vigorously pursuing happiness. Yet I certainly see owning a home as an often great thing in the ebb and flow of our lives, provided contextual issues are properly considered and addressed.

Skipping Over the Past

I could dedicate more Dividend Cafe time and space to the great sin of the financial crisis if I wanted to, and in fact, I have covered underlying issues about that point in time more exhaustively elsewhere. But that point in time in which people believed buying a home was a risk-free means of making free money, where they thought down payments and equity were for suckers, where they thought social strata were achieved through one-upping their friends in the neighborhood or home amenity bragging rights, all of those things are old news. Now, “thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house” is super duper old news (Exodus 20:17) – and there is nothing new under the sun – and what is old often becomes new again. I do not think 2008 rid us of “FOMO” or “keeping up with Joneses” – even if the instruments of expression have varied and rotated over the years. Human nature is immutable and all that. But today, I think we deal with a larger problem in our view of housing than the views of 2002-2006.

Compare and Contrast

In the aforementioned era that helped usher in the Great Financial Crisis, I think the primary issues were, in no particular order:

(1) Naive views about the ability of homes to preserve value

(2) Wishful thinking about the ability of homes to keep growing in value

(3) Buying a home based solely on the monthly payment, with no regard for the purchase price, the total cost of ownership, terms of borrowing, or even qualifications to be a borrower and buyer

(4) A dunce-like devotion to short-termism

(5) Moral turpitude surrounding obligations, characters, and contracts

Today, I believe we are facing a housing crisis worthy of this edition of Dividend Cafe, but is not a crisis of imminent crash or a crisis of systemic financial conditions. It is not a crisis rooted in one borrower’s rank irresponsibility and another lender’s rank stupidity. It is less short-term focus and more long-term side effects.

2023 is not 2003. But there is a big problem in 2023.

A Crisis of Affordability

I believe that we have a housing market that is way too expensive because of (a) Under-supply, (b) Under-supply, (c) Low quantity of household formation as more young adults have extended their adolescence by a decade or so, (d) Under-supply, (e) Later marriages which are connected to item C in this list, (f) The embedded expectations of a lower anchored interest rate for borrowing cost, and (g) Under-supply.

But we have a far bigger crisis than how expensive homes are, and that is how much our society prizes them. People love it. People think it is awesome. And it is pretty hard to change a problem when people not only don’t acknowledge there is a problem but actually think the problem is a feature, not a bug.

Why do people celebrate expensive housing? (A) They are under-funded in their own savings and investing and view home price appreciation as a substitute; (B) Ego and pride; (C) See A again

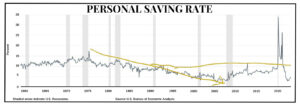

Our national savings rate was robustly and consistently above 10% from World War 2 until the early 1980s, often reaching closer to 15%. Since then, it has consistently stayed well below 10% and got to a 2-3% level in the years just before the financial crisis. What kind of sucker socks away money in the bank when they can be flipping condos in Vegas, baby?

The spike in COVID is an outlier from government transfer payments, but taking away that statistical anomaly, you can see we remain in a very low savings environment, part of a multi-decade trend that, not coincidentally, dovetails with the national obsession with home price appreciation.

So a lot of people love feeling that their safety net is not in their couch cushions but in the house that holds their couch. And a higher value of one’s home makes them feel richer, more secure, and all that kind of stuff. For some with high equity in their home but low value of savings and investments, it will likely be the source of their retirement income. This is all better than the alternative (the only thing worse than no money with some home equity is no money with no home equity, I suppose).

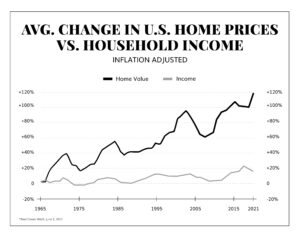

I mentioned in DC Today a week or so ago (and you can see it in the Chart of the Week below) that home prices are up +118% in the last sixty years (NET OF INFLATION). Some point out that “yeah, but, the houses are bigger now.” And as we shall soon see, that is completely immaterial to the point I will be making. A median home price was 2x median income ~40 years ago, and it is over 4x median income now. The issue is not the size of the home one is getting or the size of homes that are being built. There is another trade-off at play that has to be understood.

But the idea of a birthright to a high and ever-growing value of a home comes at a cost. That cost is cultural, and all cultural costs are economic because humans act.

A Crisis of Loneliness

We are said to be living in a period of real loneliness in our society. The data validating increased feelings of alienation is impossible to ignore. On one side are the extreme cases of despair that are too ghastly to talk about, but even in more moderate cases, we have the socially undesirable outcome of people often being alone, being less connected to a community, and candidly, watching way too much &*^% cable news.

Increasingly, the high cost of owning a home is creating a dynamic of never leaving one’s home. So much more disposable income is going into owning a home that that much less disposable income is available to spend money outside of it.

Was the American dream to own a home and spend 50% of one’s after-tax cash flow in paying the bank for the borrowed money that provided it, with little or no money left for vacations, dining out, community activities, and so forth? I am quite on the record as to what I think about the [now recognized as such] debacle that “work from home” has been, but isn’t it all part of the same issue? More and more things are pushing people into the alienation of their own homes and keeping them away from activity, engagement, and connection. How can this not be a culturally concerning development?

Culture and Economics are not that Separate!

But it is an economically concerning moment, as well. A low savings rate leaves us fragile and exposed to downturns and distress. A high fixed cost structure removes the flexibility that is embedded in discretionary spending. Cultural movements towards isolation make people less date-able, which makes them less marry-able which impedes household formation, which, by the way, impedes new housing supply, which, by the way, increases housing costs, which, by the way, increases staying at home in isolation. And I could go on and on and on. Like almost everything in economics, we are either creating negative feedback loops or positive ones – vicious cycles or virtuous cycles. The negative feedback loop we are in with housing is fed by unaffordability, and yet the result of it all (full cycle) is enhanced unaffordability.

What is being missed in a CULTURE of artificially elevated housing prices is an ECONOMY that is losing productivity constantly. We are not producing the goods and services we need to meet the needs of humanity, and we are not innovating and enhancing our quality of life as we could because far too many are living on a rent payment or mortgage payment that is beyond the scope of reality, and sacrificing social, family, community, external, and civil dimensions that are making life less pleasant personally and financially.

The Solution is Still in Freedom

People should be free to buy a home when they want, at a price they select in mutual agreement with a seller. If prices went higher in organic, healthy, and natural ways, it would be part of a market economy going through the natural process of price discovery and finding price equilibrium. It would be healthy, and it would warrant no cause for commentary for me. There are plenty of things out there that I think cost more than they should (almost every single thing my kids buy, for example), and plenty of things I would pay way more money for if I had to (Chinese food comes to mind). But I don’t think I have a superior grasp of price discovery – I just accept that markets and subjective values are the best way of finding accurate prices over time.

In the case of housing, we are choosing to use a brutally low supply of housing stock and the policy tool of a disinterested third party (the interest rate of the Federal Reserve) to determine housing prices (or largely influence them). We use a worldview of NIMBYism (“not in my backyard”) to ensure that property values are pushed to the highest possible, and we think it is a good thing. And we are doing so believing that it is making us richer.

It is not. It is making us poorer. A rich society is one where there is ample economic activity taking place, not just the obnoxious tour of one’s home to show off their newest house toy or design feature (spare me, please). There is a world of things to do and spend money on that transcends one’s home.

Morning in America might well begin down the street.

Chart of the Week

Data was explained above. The chart speaks for itself.

Quote of the Week

“What is happiness? It’s a moment before you need more happiness.”

~ Don Draper

* * *

Markets and banks are closed Monday, so we will be back at you Tuesday with an extended edition DC Today. Reach out with questions, and enjoy your weekends – in and out of your homes.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet