Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

It has been a year and a half since I first took up the inflation/deflation debate as a matter of contemporary debate (a part 1 and a part 2). As much as I wished then (and now) that the great economic fight we would have for the next thirty years was inflation, I believed then (and now) that the great economic fight we will have for the next thirty years is better referred to as deflation (a term that itself will require more precise explanation). Some more in-depth updates on the subject have also been produced with a deep desire to really explain and contextualize the state of affairs. I doubt there has been a DC Today or Dividend Cafe since the post-COVID inflation run began that some aspect of this subject was not covered in some way.

Nevertheless, the responsibility of clarity in messaging is with the writer, not the reader, and while there is only so much I can do to make sure those reading it understand it, I have a pretty strong desire to keep doing more. And I certainly believe that one reading the headlines about inflation (or, I don’t know, actually buying something at the store) could be forgiven for hearing that I see our multi-decade battle as different than the inflationary one we see now. Because of the tension between the present price level and my claim about the systemic economic battle we face, I think a new clarifying and clear attempt at total clarity and clarification is in order (see what I did there).

Let me just leave the introduction there and dive into this topic. I suppose I do hope some clarification comes out of this, but truth be told, I am more passionate about just reiterating the great economic message of our time. My agenda is not academic, and it is not political. I am responsible for actual client capital, which is to say, the instrumentation by which actual human goals and needs are met. I take it very, very seriously. And this subject sits at the center of what I believe is a generational economic challenge. This is not about how people perceive or understand or interpret me – it is about a message of economic reality.

Let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

What this isn’t

Let me start with what I am not doing in this Dividend Cafe … This is not a mea culpa. That is not because I am against admitting it when I am wrong, and it is certainly not because I am not capable of being wrong.

The list of people in macroeconomic forecasting and investment market prognostication who are never wrong is exactly zero. The list of people who are exponentially smarter than I am who have, on occasion, been profoundly wrong about a significant take includes every financial legend you could possibly name. Being wrong about something in this profession is not just likely; it is assured. The objective intelligent and prudent asset allocators have is to learn from mistakes, and to limit the damage from mistakes through prudence and wisdom in one’s process and execution. There are a lot of tools for how one can “be wrong without doing much harm,” but I will save that for another Dividend Cafe. For now, I am merely trying to make the point that great financial minds get things wrong, and then so do mere mortals like me.

So if I felt that there had been a systemic mistake made in my assessment of long-term economic reality here, I would absolutely fess up. It is a serious and deep commitment of mine in this profession (and in my life, more broadly speaking). I wrote a book on the crisis of responsibility in our culture. And furthermore, whatever “mistake” would have been made over the last 18 months on this subject has hardly impacted our actual portfolio management. Our dividend growth portfolio, which is the bread and butter of what we do, is up substantially in that period, far far outpacing broader equity markets. Our highest sector allocation has been the top performing sector in the market for 18 months. Our avoidance of crypto and “shiny object” tech has avoided unfathomable losses. Broadly speaking, we are extremely happy with how we have done. So if there was a “commentary” call that warranted reversal, it wouldn’t be one that had damaged a “portfolio” call (therefore, why not fess up if it were true?).

I will write a book of mea culpas someday, and I certainly do my best to own the mistakes I make in forecast, analysis, or conclusion. I do so because it is unavoidable in my line of work, and because it is the right thing to do.

Now, let’s qualify this a bit

Some aspects of what has happened over the last 18 months have gone differently than I expected. That is not the subject of this Dividend Cafe. At one time, I did expect the Fed to get to 1% or 1.5% and chicken out on raising rates. But in the immortal words of my least favorite economist of the 20th century, John Maynard Keynes, “When the facts change, I change my mind; what do you do?” I am sure if someone asked me what the CPI would be in the summer of 2022, I would have said something lower than it is now, but I am and have been throughout focused on the secular reality at play.

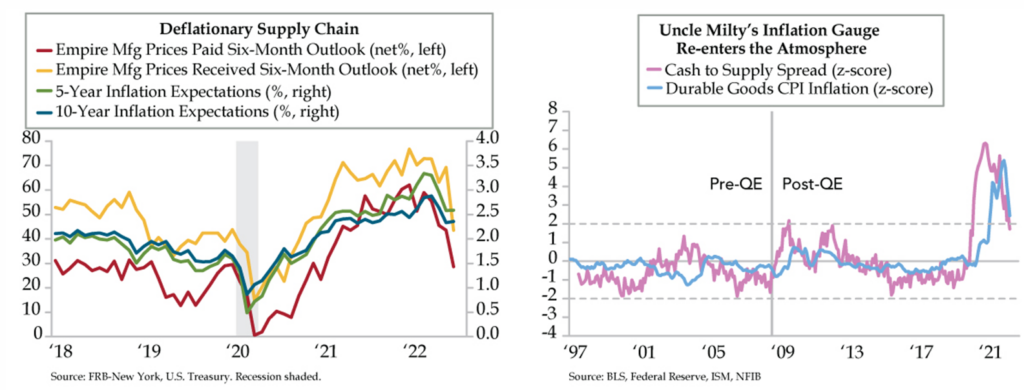

A debate without a scoreboard

When one debates something like what is causing a certain event to happen, it is useful to the cause of epistemic humility to remember that there is not really a way to solve the debate. We can acknowledge price increases without agreeing on the cause of price increases. Some can give more convincing arguments than others, and some may have more anecdotal support, but there is a “non-falsifiable” component to much of this. My assertion is that the lion’s share of price increases over the last 18 months have been supply-related – that is, an inadequate level of production to meet needs, thereby pushing prices higher.

Suffice it to say, I think the better arguments are on my side than with those who would suggest it is primarily demand-driven (that is, excess money inflating demand for goods and services, therefore pushing prices higher). I think the debate is important, and I think the evidence is overwhelming for my side of this causation debate. But in all humility, if one wants to disagree about causation, it is not empirically provable, and life is short.

Demand inflation in housing

I believe that artificially stimulative and distortive monetary policy combined with a broken social calculus around the purpose of housing layered on top of a deeply problematic supply process for new home construction (regulatory, environmental, etc.) has, indeed, inflated the hell out of housing prices. This has been a consistent theme in my writing for 20 years and is, in this case, the exception that proves the rule. Low rates are easy to identify as causation when the thing being bought is levered 4-to-1 – and when the cost of such leverage going higher leads to an immediate reversal of the price inflation. Interest rates are up substantially in 2022, and housing inflation has completely and totally stopped (and will soon reverse).

Have higher rates stopped food inflation, energy inflation, or travel inflation? No, because low rates were not the cause of that inflation, to begin with.

If all one wants me to admit is that monetary policy, government policy, and various other social circumstances have recklessly inflated housing prices, I not only admit such but have been saying so for years and years and years. And I believe that a reversal of unnatural price appreciation in this sector is a good thing, not a bad thing. And I think this is obvious.

Okay. But what are you saying is the cause?

First things first. Assumption #1 is that “huge bouts of government spending caused helicopter money to float around and boost inflation.” I want to offer assumptions that I think are better explanations in the current moment. But I think the main points I have tried to offer throughout this period of time regarding the role of government spending in creating inflation are as follows:

(1) When additional government payments to the citizenry do get spent, and do boost demand, they do not sustainably boost inflation. At best, they are a sugar high. They come with a collapse in the velocity of money (its ongoing turnover), which always puts downward pressure on inflation over time, but with an even worse side effect – the debt that such government payments created.

(2) While it can be a fair argument that this $2 trillion batch of government spending was different, one simply has to somehow contend with how the last $20 trillion of government spending somehow wasn’t.

(3) Ummmm, Japan. More on that later.

When one like me suggests that government spending is not the most likely culprit of inflation, I do not do it to speak favorably of excess government indebtedness. I cannot emphasize this enough: I believe what I am asserting is a more negative assertion than what the inflationistas are asserting. More on that later.

Okay – so what am I suggesting was the primary cause of inflation over the last 18 months? The key word is “primary” because there are certainly a multitude of plausible explanations, and in all likelihood, the answer is found in the multitude. But I would suggest “supply” constraints rooted in the following are the Occam’s razor of this whole escapade:

- Semiconductor shortages that have become detrimental to everything from electronics to automobiles to appliances

- A COVID re-opening that was massively under-estimated by everyone who doesn’t understand humanity

- Massive labor shortages caused by extended federal unemployment benefits, excessive federal government direct payments, a pandemic period of complacency and anxiety, and social and cultural factors that have been covered in other Dividend Cafes.

- An under-investment in U.S. energy production combined with overreaction to demand erosion for energy out of the pandemic

- Intermittent lockdowns throughout the re-opening constrained manufacturing capacity (here in the U.S. and especially in China

- Poor policy administration at ports responsible for receiving and distributing cargo

Neutralizing politics with better signals

My assertion for some time has been that many have brought a political motivation to their treatment of this subject over the last 18 months. I am almost entirely sure that I have been successful in resisting such a temptation (I say “almost” because my dad raised me to be painfully aware of our own propensity for self-deception). I am, personally, a movement conservative who leans center-right on most political issues, and I do believe the current administration is culpable for much of the current inflation. But I have believed that because of supply failures in energy production, and I have believed that because of incentives their spring 2021 spending bill gave to not work; I have not believed it because of the standard conservative talking point around the spending itself.

It is easier for me as an asset allocator and economic strategist to have a more objective way of evaluating inflation causation and expectations.

I submit to you, that we have such:

*Strategas Research, Policy Outlook, July 19, 2022, p. 1

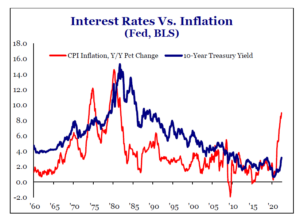

The bond market is not God, but it’s not man

As I type, lenders are giving their money to the United States government for TEN YEARS for 2.8% per year. Does that sound like a high expectation of inflation into the future? Friends, it not only doesn’t sound like much expectation of inflation – it doesn’t sound like much expectation of growth, either (more on that later).

But the Fed?

The Fed started tapering its bond purchases in December (seven months ago). It stopped them entirely in March of this year. Since that time, the 10-year bond yield is lower, not higher. The exact same thing in the years following the end of QE3 took place. Rinse and repeat. Our Fed was not the reason for low bond yields out the curve.

A collapse of expectations for growth is the reason.

And this is the subject of part 2 of this next week.

Conclusion:

I said “more on this later” a few times this week. I have to wrap this week now but want to come back to you next week with the following:

(1) An explanation of what Japan teaches us about this very subject

(2) An explanation as to why I believe that disinflation will again become the predominant economic narrative

(3) An application as to what the real takeaway of this whole subject is.

Chart of the Week

What goes up comes down in a secular era of disinflation.

Quote of the Week

“The problem is that credit is debt — and paying debt service to bondholders leaves less income available to spend on goods and services. So debt-deflation is today’s major problem, not inflation.”

~ Michael Hudson

* * *

I prefer to keep Dividend Cafe from 2,000 to 2,500 words each week, and once I passed 2,000 words this week, I realized I was not even halfway done. So now I have to go and finish the next 2,500 words from California next week. I am as disappointed as you are, I am sure. =)

I believe part 2 of this is extremely important not just for investors, but for all citizens and economic actors. And I write out of an intense care for the cause of economic growth, not any sense of personal vindication, something that means nothing to me whatsoever. But economic growth. Investment coherence. Human flourishing. To those ends, we work. In fact, I will take whatever inflation of THAT I can get.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet