Dear Valued Clients and Friends –

I think there is some “economic vocabulary” in today’s Dividend Cafe that might – might! – be a turn-off to some, but will be overcome easily if you bear with it. And more importantly, there is a practical takeaway through it all that I hope you will find very rewarding.

I can see myself taking a more “multi-topic” approach to Dividend Cafe in the weeks ahead as opposed to the last several that have purposely “drilled down” into a particular theme that warranted special focus. That said, I find that five or six different topics seem to have a lot of overlap these days. I can think I am talking about government spending one paragraph and economic growth another, and voila, the third paragraph is talking about how government spending impacts economic growth. Economic and market commentary these days is one giant Venn diagram.

Such is the case with so many things I cover today. I prefer writing where all the dots are connected by the end, and maybe you will think I pulled that off by the end. But what we have today is a lot of charts, a good amount of information, some perspective that I confidently believe will aid your understanding as an investor, and maybe, just maybe, some cohesion to it all that adds sensibility when said and done.

The false dichotomy of our day

It does feel like most economic conversations right now center around the choice between (a) A weak economy that can’t get going because of COVID and low demand for services, etc.; and (b) A “too hot” economy that risks inflation because of all the money sloshing around additional government stimulus that causes things to run hotter than they ought (the informal term for what Larry Summers says would be “injecting more than the amount of the output gap.”

I am in the “none of the above” camp, and I want to explain what this all means, and why I believe an option C or D is more likely.

The Gap isn’t just a place to buy clothes anymore

My friend, John Mauldin, had a little discussion on “output gap” in his weekly newsletter last week, and it got me thinking about something. First of all, the “output gap” is what we call the difference between actual GDP and “potential GDP.” An economy running below its potential has an output gap, and an economy running above its potential is “running too hot.”

But did you notice what I just said? “An economy running above its potential.” Isn’t there something inherently contradictory about the very phrase? For those who wear a heart monitor or some such device when they work out, do you ever see your tracking tell you that your heart rate was “over 100%” of its maximum? (my fellow struggling Orange Theory zealots know what I am referring to). I assume we all know the tautology involved that your heart rate cannot go over 100% of its maximum because if it does, it means we had the maximum wrong. Likewise, if an economy is running “above its potential,” does that mean we under-estimated its potential?

Well, in this case, the problem is the vernacular, not the concepts themselves. The measurement of “full potential” solves for productivity and growth at certain full employment assumptions. Because growth is defined as GDP growth, and GDP is a formula that contains a number of different things, you can at times get a GDP reading in excess of what assumptions were in terms of full productivity. But this says more about the measurement of GDP than it does “potential economic growth” – especially if we shift the conversation to “productivity” (which is what this supply-sider cares about).

When the economy has an “output gap” (less economic growth than there is potential assuming fuller employment), it is almost always because either (a) We need more employment, or (b) We need more productivity from that employment. We had a mostly employed labor forced from 2017-early 2020 (pre-COVID), but we still had an output gap because the potential for more productivity (out of more business investment, CAPEX, etc.) was quite high.

But right now, there is some concern with all the government spending that we may add more to the economy than the amount of the output gap itself, and that would “create inflation” (one term being used) or cause the economy to “run too hot” (another term for it, which as best I can tell means the same thing as the preceding one).

All fair enough. Except that one problem about maximum heart rate.

We simply HAVE to be able to distinguish between productive growth and non-productive growth. I cannot ever say this enough. Econometrics that are designed to measure “growth” fail in their ability to give us actionable information if it treats economic growth all the same. An economy of great innovation and investment may run “above potential” but then see goods and services created that “soak up” money supply, thereby being non-inflationary and moving the needle on “potential GDP.”

But on the other hand, an economy growing on paper, but around other metrics that do not represent real wealth, real prosperity, real invention, real appetite for goods and services, real production, real supply, real activity – that is an economy exposed to “running hot” – where the growth appears to exceed potential, and distortions and inefficiencies surface all over the place.

So an output gap (“slack”) is what we are told happens when there is inadequate demand in the economy, and therefore can be solved by stimulating demand either through more fiscal spending or more access to credit (lower interest rates, etc.).

Inversely, if there is more demand (of people wanting to spend money) than supply (of goods and services), we are told we have inflation. Fair enough.

But just as the person exercising is, theoretically, always moving what their physical conditioning marks might bear (if you think the max heart rate is the same for a 250-pound guy as it is for a 200-pound guy, I have a bridge to sell you), so the measurement of “growth” and “potential growth” is a moving target. We cannot measure what we need to measure without a distinction between productive growth and non-productive growth.

Our max heart rate goes up, as the thing we are doing to lift our heart rate takes hold. We get in better shape and can bear more exertion.

So it is with potential GDP. PRODUCTIVE economic growth pushes the envelope of productive economic growth.

Government spending and your heart rate

If I haven’t lost you yet, maybe this will really get your heart rate up. Yes, most of us fret about government spending that seems to exceed logic and common sense, especially if and when we think about that debt being paid back. One of the problems economically is that conversations around government debt are always framed politically. It may be a legitimate argument to say, “my kids will be burdened with future debt” (legitimate and true), but it actually deflects from the economic point while making the political one. And the economic point is that irrespective of how debts get paid back by future generations, the productivity in the economy of government spending is not the same as other inputs to the economy. It distorts our understanding of the “output gap.” It gives us a bad read on our heart rate monitor. It does not differentiate between productive and non-productive. Etc.

Wrong on both sides

Therefore, we end up with the potential for two errors. One, is that we prepare for an inflation or “heat” that never surfaces because the way government money is spent does not cause the economic output to actually grow.

But the other is that we assume the non-inflation of this government spending means there is nothing to worry about, when in reality, it undermines the productive growth we are trying to get (i.e., remember – filling that “output gap”).

What does this mean for my portfolio?

I have not laid all this out to provide a merely academic or intellectual case for a certain economic theory. This is actionable stuff. We formulate expectations around macroeconomics, around supply conditions, around business expectations, around trade – around all the inputs that actually at the end of the day end up determining corporate profits – around these things we are talking about.

What companies and what sectors are likely to create what profits in what relative competitive context (etc., etc.) flows out of all of this. This is not armchair stuff – it drives the things that create results (either in asset prices or, more specifically, the cash flows that actually create asset prices).

P.S. – you can’t get your heart rate up sitting in an armchair.

Speaking of debt

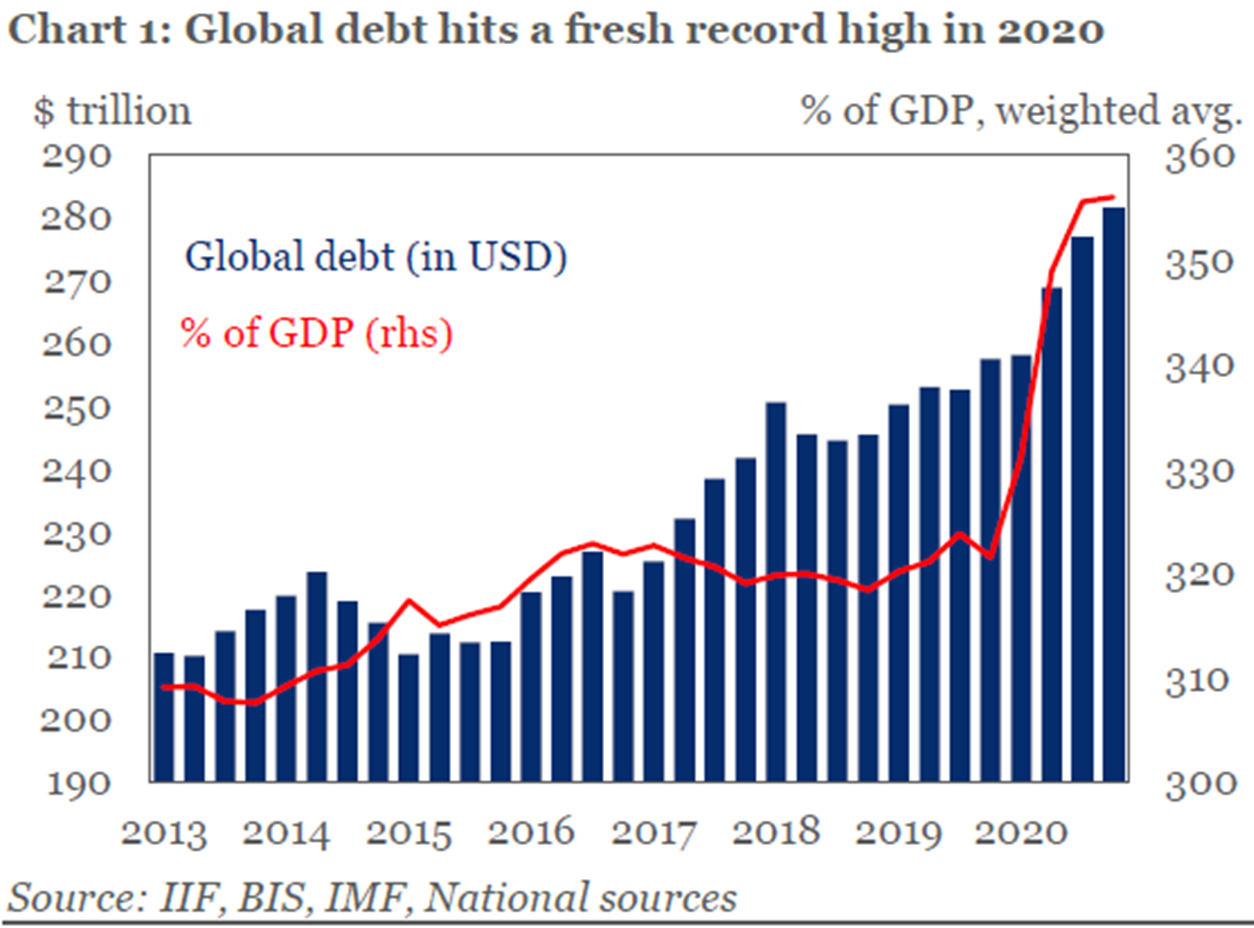

I think one of the most important things I could say about the entire conversation regarding debt is that: (a) It is not just U.S. debt that has exploded in recent years, but all global debt; and (b) It is not just government debt that has exploded in recent years, but corporate debt. Now, some significant distinctions are important here, but some similarities need to be highlighted as well.

Corporate debt exploded post-financial crisis as the Fed used monetary policy to promote credit, and companies followed suit. Why was this not inflationary? They did so productively. The debt came with a high return. Mostly.

It also enabled non-productive companies to survive. Companies that couldn’t compete anymore could stay alive because they had access to cash to keep the lights on.

So you end up with a tale of a lot of cities. Some productive companies using debt to leverage great profits and growth. Some non-productive companies using debt to perpetuate a misallocation of resources.

And countries using debt to facilitate public spending that diminishes the productivity of capital as it is extracted from the private sector.

What do all these things have in common – the countries and the companies, the productive and the non-productive?

A diminishing return over time. And a debt that is still there, even when its return product diminishes.

Unpacking the spending

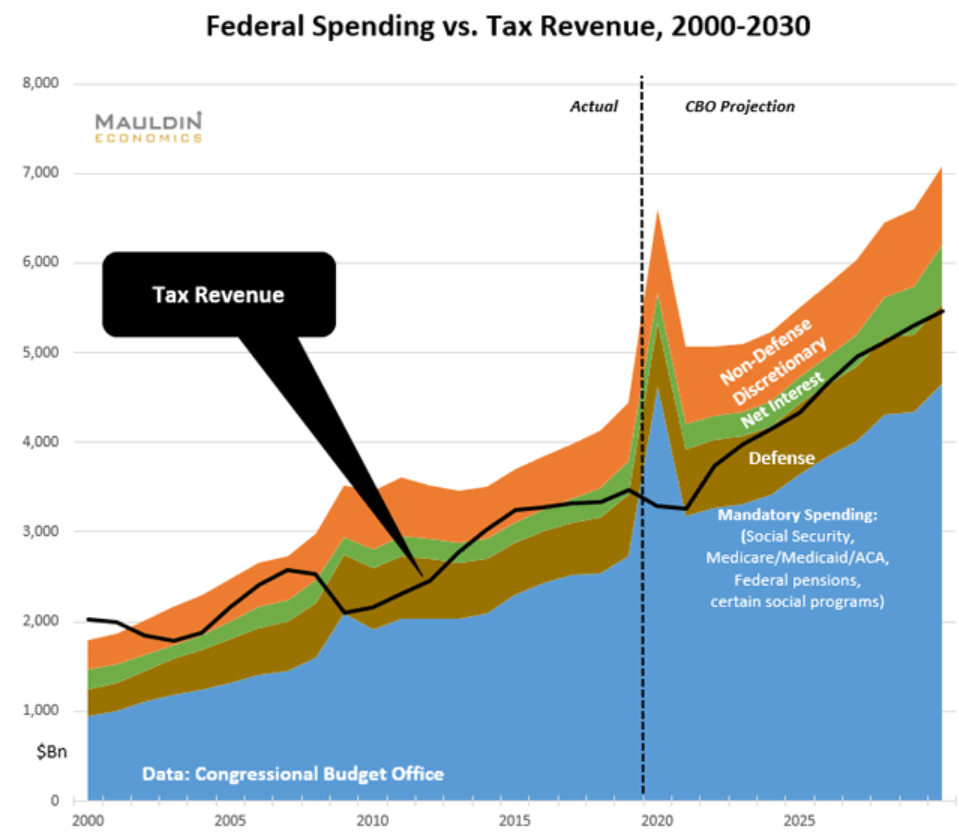

Critics of government spending often talk as if the interest on the debt is going to kill us (and certainly, a cost of debt that is 7% would be a lot worse than the current sub-1% cost of debt). And critics of government spending generally feel that if this department here and this bureaucracy there could be struck, we could solve for our fiscal woes.

I’m as big a critic of wasteful government spending as the next guy, but we have to candidly appreciate what is the reality is when we think about the future of government spending and its role in our economy. Discretionary spending and interest expense are a small part of government expenditures.

Some odds and ends …

In defense of big tech

If that headline were the title of this Dividend Cafe, you could probably accuse me of click-bait. I am well on-the-record for my belief that we have valuation concerns when it comes to the FAANG/big tech names that have served as market leaders the last couple of years, at least when it comes to calculating a risk-reward relationship. I do have concerns about general behavioral patterns that look and feel like past manias and bubbles – as I have documented in recent Dividend Cafes.

But I also feel that I have been rather clear about key differences between current circumstances and 1999, as well. Revenues and Profits at the five biggest tech companies are massive – and I mean massive. Now, is their massiveness reflected in their P/E and P/S and P/B ratios? Certainly. And then some? I suspect so. But for one who does believe:

(a) Valuations eventually matter, even if it takes a long time

(b) Froth comes when indiscriminate investors come, and does not end well

and

(c) Leadership names of one decade or period simply do not repeat as leadership names of the next decade or period – at least not historically …

… I have to make sure I credibly and thoroughly report all facts around this situation. In other words, because I think the lessons in those above three points are so true and so important, I also want the right caveats and intervening facts to be made clear.

Plenty of non-FAANG tech companies might have certain commonalities to 1999 Nasdaq conditions right now. And the FAANG companies themselves have legitimate and debatable questions about valuation. But there is no comparison to the profits and revenues of the 1999 leaders to these cats today.

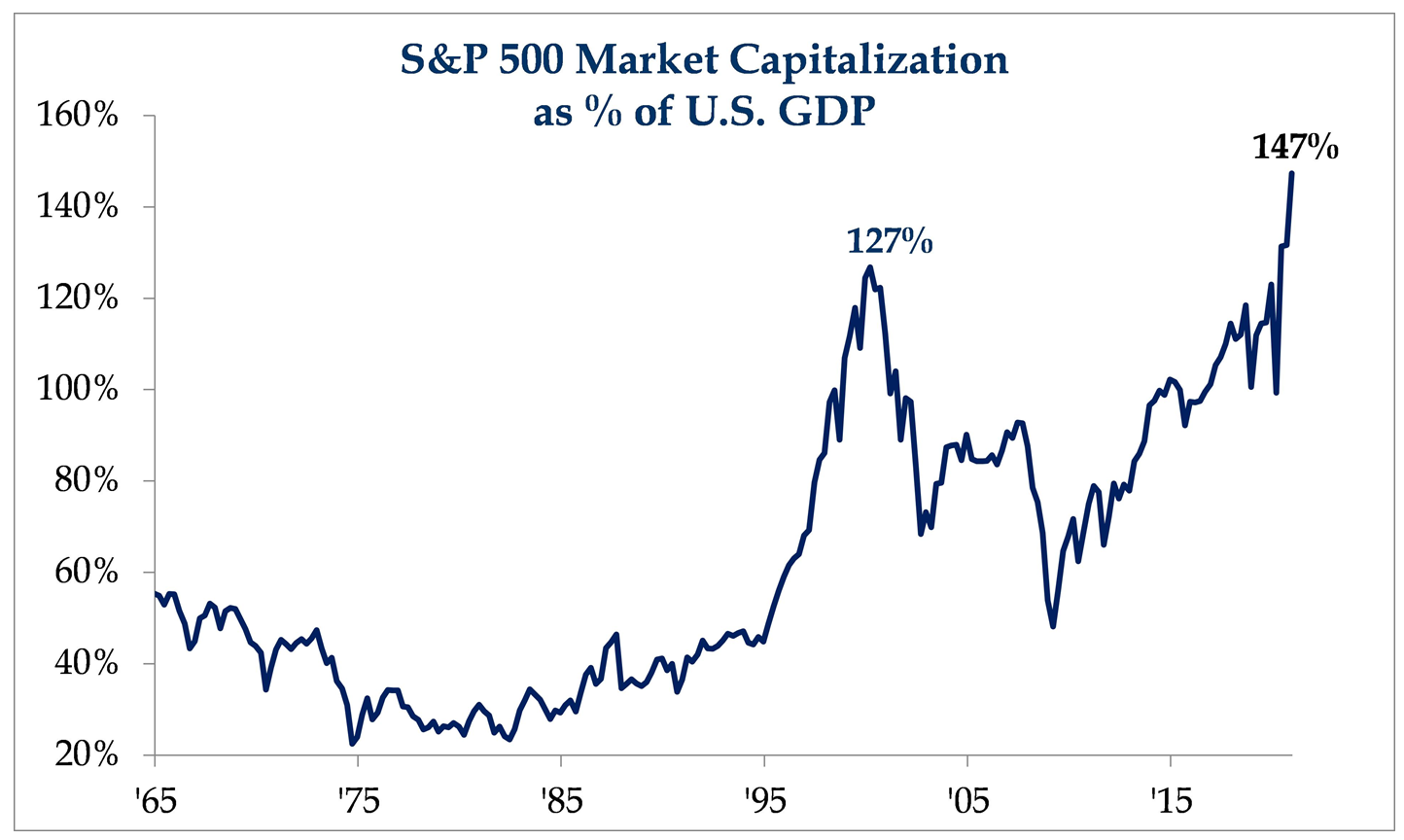

Buffett Non-Indicator

I have been as vocal as anyone could be about potential valuation concerns in the market, but the one area where I am far less provoked is the so-called “Buffett indicator” (total stock market capitalization to GDP). Yes, this number is at a record high, but unlike past pre-recession peaks, this is post-recession, meaning the GDP number is the low one, causing the market number to be the high one. Now, market levels are high, of course, but these percentages are misleading as the economic recovery we look forward to in the months ahead resets them. The reading will still be high, but the use of this metric to past comparables is, right now, an apples-to-oranges mistake. I would note, for a metric that is supposedly Buffett’s favorite, you should note how much (and what) he is buying these days! Apparently, Buffett is not concerned by the Buffett indicator.

*Strategas Research, Daily Macro Brief, Feb. 19, 2021

Chart of the Week

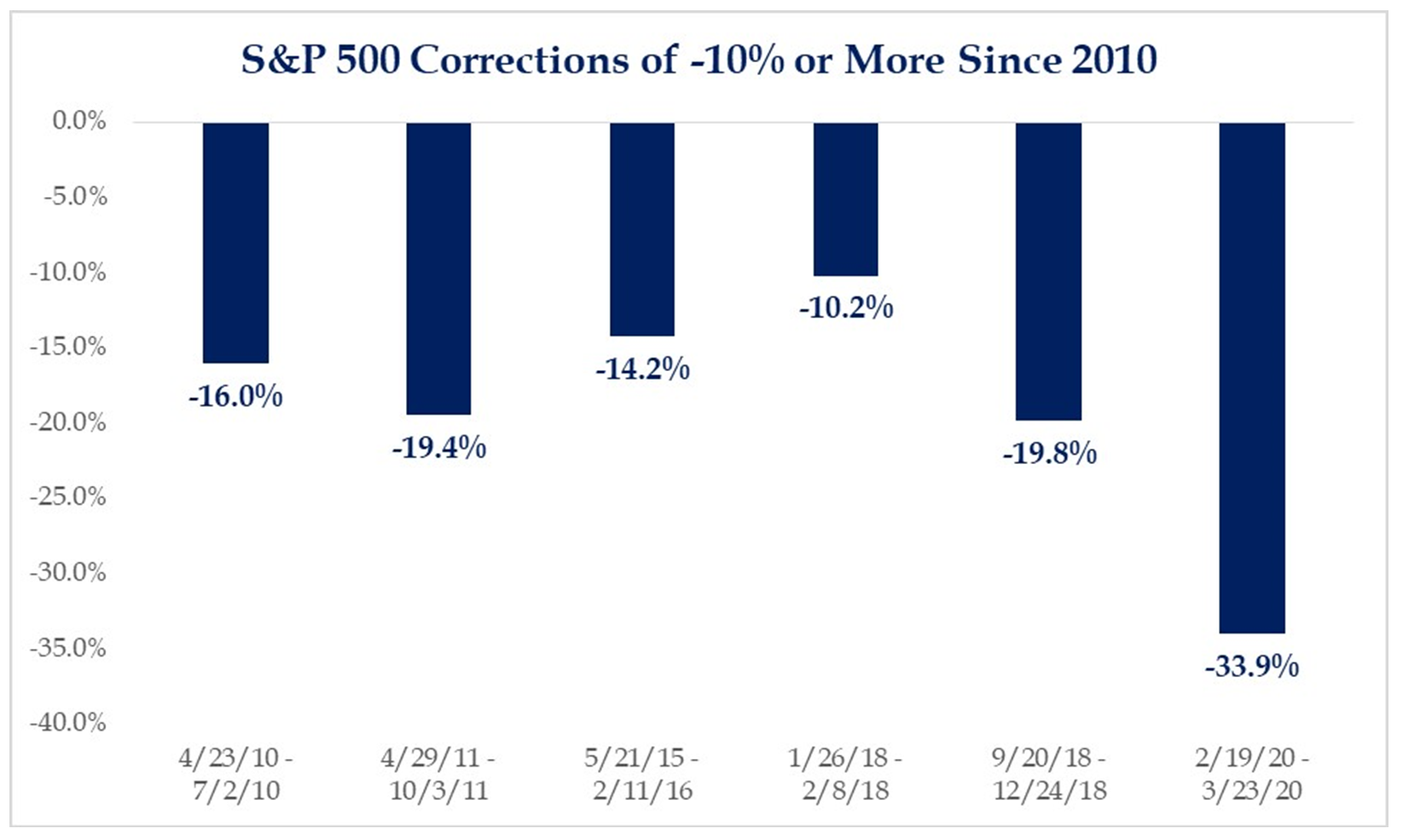

I imagine there will be two camps of investors should this strong equity market position continue for a while – those who build a complacency about the reality of market downside volatility, and those who continually fret about downside market volatility.

Both are in error.

Corrections will come. Note the SIX different times the S&P 500 has declined over 10% in the last decade. This level of decline doesn’t just happen; it is reasonably routine.

And of course, note that the broad market has more than tripled from the start of this period through where we are now, despite six incidents of a decline ranging from 10% to 35%.

*Strategas Research, Investment Outlook, Feb. 16, 2021

The #1 mistake one can make about market corrections is forgetting that they are inevitable; the #2 mistake one can make is thinking they can time their way in and out of them actually. The #3 mistake one can make is panicking out of a properly-built portfolio when they do happen.

The right allocation and portfolio construction is one that, at worst, does not see financial goals fazed by inevitable market corrections. And at best, actually benefits (to that end, we work).

Quote of the Week

“How is it possible to expect that mankind will take advice when they will not so much as take warning.”

~ Jonathan Swift

* * *

I am off to New York City tomorrow for a few weeks of pretty intense meetings, study, work, and portfolio adjustments. From the sunshine to the snow … this is the life I chose.

Please join us for our bi-weekly national video call on Monday, February 22nd, at 11:00 AM PT / 2:00 PM ET.

I welcome your questions and comments as you unpack this week’s Dividend Cafe. Have a wonderful weekend! I hope to ramp up my heart rate monitor a bit …

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet.