Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I plan to make this the last “extra” Dividend Cafe, but only because I am adding a daily missive at COVIDANDMARKETS.COM that will last as long as is necessary. Dividend Cafe will still come every Friday as it has for nearly 12 years. But the need for daily, timely, sometimes granular health data, market impact, and policy response has necessitated me formalizing and organizing that content into a different web property. If once a week is enough for you to hear from me on markets and such then feel free to just maintain the status quo Dividend Cafe receipt to your inbox. If more granular and consistent information and perspective is your preference, go to the new site each day for updates (we won’t flood your inbox daily, though).

This last “early week” Dividend Cafe is one I heartily recommend if you are interested in better information on market behavior over the last six weeks, an investigation into the truth about stock buybacks, stop-losses, the Fed, oil, and ultimately, a treatise on the science of optimism.

Jump on in, to the Dividend Cafe …

First half of the week

As markets are closed for Good Friday, we are now 50% of the way through the market week. A nearly 1,700 point up-day Monday was followed by another big rally Tuesday (up 900 in the morning), with that rally eventually lost by the end of the trading day. Markets are excited that much of the health data and left-tail risk has improved, and in other cases, is now tracking to improve (even if the improvement is in the future, not present).

Market Timing

A few market factoids I want to share to pull together for making a point of application:

- The drop in the S&P 500 from February 19 to March 23 was 33.9%, and as I have commented several times was the fastest such drop in market history

- The increase in the S&P 500 from March 24-30 was 19.2% and was the second-biggest five-day move higher in market history

- 18 out of 21 trading days in March saw the S&P up or down more than 2%. That is 86% of the days were up or down over 2% (I don’t have any memory of the three days that weren’t, by the way). From those 18 days, and this is key, eleven of them were down more than 2%; but seven were up more than 2%. Timing in and out would, ummm, have added to the risk.

- In those 18 days, we experienced the two biggest point drops in market history (one of which was the second-biggest percentage loss day ever, second only to Black Monday 1987). But we also experienced the biggest daily percentage gain since 1933.

The information above is shared for two reasons: (1) To provide context and historical appreciation for the level of insanity we are living through, and (2) To provide crystal-clear support for why the maintenance of a properly constructed long-term asset allocation vs. wholesale piling in or piling out of risk assets is the proper wisdom at this moment.

As was stated in a recent investment letter, “I can’t believe I used the words ‘panic’ and ‘fear of missing out’ within two weeks of each other.”

* (H/T Howard Marks for many of these nuggets)

Now THIS is fascinating

Why are “stop losses” and market trading and other such fictitious mechanisms of giving one the illusion of control such a fraud and counter-productive avoidance of the real risk that is a part of being an equity investor (especially in a generational hyper-volatility like we experienced last month)?

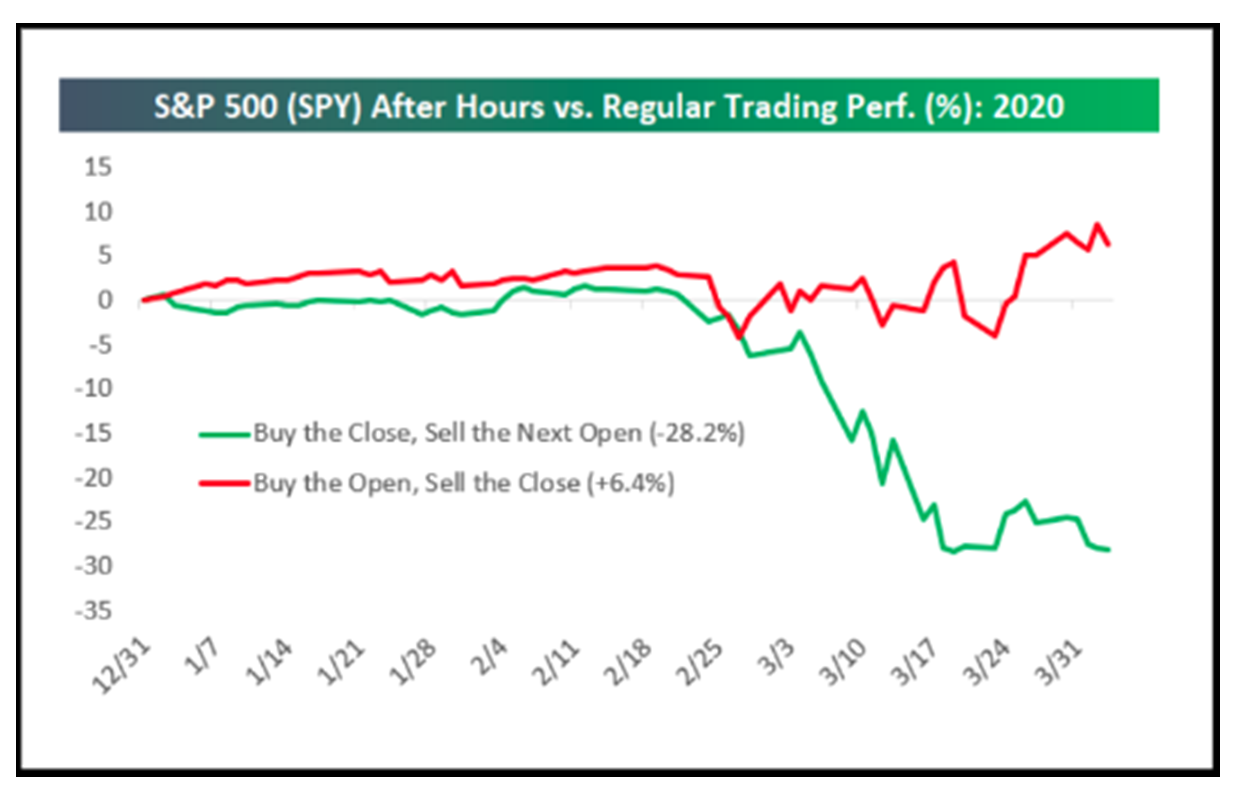

Because all of the action is AFTER market (or BEFORE market), anyways! This chart is just absolutely fascinating to me … Just referring to market hours themselves, the market is actually up on the year! It is the -28% that hasn’t happened between the close each day and then open the next day (in aggregate) that has net-net provided all the carnage. Markets opening down at big gaps explains most of March’s bloodbath. Obviously plenty of selling off in market hours took place, too. And plenty of market rallies have taken place in market hours (enough to offset in aggregate). But a big reason why I have spent more time watching futures at 3:00 in the morning the last month than I ever did in the financial crisis can be explained by this chart.

* Jones Trading Institutional Services LLC, April 7, 2020

A relationship that doesn’t exist

A media narrative is forming that needs to be addressed around stock buybacks. The story goes – companies are eliminating stock repurchase plans in droves (certainly true), and the stock market going higher has been dependent on companies purchasing back their own stock (certainly not true), ergo stock prices are in trouble without buybacks.

Stock buybacks were $100 billion higher in 2018 than in 2019. In 2018, with the highest level of stock buybacks ever, the stock market was down over 6% (first down year in a decade). In 2019, with stock buybacks dropping $100 billion, the market advanced over 25%.

Proper capital stewardship in the form of after-tax profit distribution to shareholders (or other use of after-tax capital, such as capex or debt relief or acquisitions) contains many different objectives, criteria, risk/reward calculations, and results. There is not a set playbook for it, and no formula that says stock buybacks from companies always help or always hurt. What most people banging the stock buyback drum never seem to realize is that the vast majority of buybacks have always been a backdoor form of executive and employee compensation, not a “pillar” to support the company stock price.

Earnings drive stock prices, and corporate earnings are preparing for a painful quarter or two. Stock prices reflected this reality in February and March, and uncertainty lingers over how far we have to go (uncertainty over the earnings impact themselves, late-year recovery levels, and sentiment applied to such). These uncertainties are legitimate; but fearing companies prudently holding back on stock buybacks is not consistent with the historical lesson.

Don’t Fight the Fed Part 10,000

Much of the Fed’s efforts to backstop liquidity and credit markets is still working its way through the system, but the following factoid blew me away over the weekend: 49 companies issued $107 billion of investment-grade corporate bonds the week of March 23. Over $210 billion was issued in the month. But in those two weeks from hell in mid-month, the idea of raising a dollar in the debt markets was laughable! The entire change was the word of the Fed’s primary corporate credit facility (supporting new issuance).

All the Oil News that is Fit to Print

As of press time, there is no substantive news on OPEC+ plans for production cuts. The Monday meeting has been moved to a Thursday meeting, and there are conflicting news reports about each side’s willingness to implement production cuts. Perhaps most crucial will be what Russia and Saudi are asking of the U.S. by way of production cuts (it is not quite so easy in our economy for a foreign country to demand that a private company turn off their rigs, and all indicators are that we are not inclined to capitulate there).

It has always seemed more likely in my analysis that Saudi would have to blink versus Russia (Saudi’s break-even is significantly higher than Russia’s from a national budget standpoint, and their rainy day fund is 60% less than it was in the 2014-15 oil war).

Do stocks want low oil or high oil?

This has been a heavy focus of my writing for over five years now. The various points I have made are more at play now than ever. On one side is the belief that low oil prices serve as a benefit to the consumer, putting more disposable income in the consumer’s pocket when they spend less on gas, etc. On the other side is the notion that extremely low oil prices threaten the profit capacity of the oil and gas sector, which threatens jobs, capital expenditures, and industries and economic activity related to the oil and gas renaissance of the last decade.

The latter camp is right here, which is why stocks and oil are mostly positively correlated these days. The performance of the stocks in the energy sector is a little less important to the overall market than it has been historically (based on how low the weighting is for energy stocks in the overall market these days), but the trickle-down effect of potential bank defaults, widening credit spreads and impacted high-wage jobs from collapsing oil prices far trumps the consumer benefit of low gas prices.

But we should even add this: what is the consumer benefit of low gas prices, right now, this very month or two? No one is flying, no one is driving, and therefore, no one is benefiting from any such thing! This merely exacerbates the positive correlation between stocks and oil prices.

Like so many things, oil prices possess a “cause” and “effect” dynamic – they reflect waning demand in the economy, but they also cause economic contraction for all the aforementioned reasons. Breaking this vicious cycle is why the stabilization of oil prices is so important to the economy.

Where does midstream fit in here?

The downward pressure on so many pipeline companies in this extreme distress relates to the market’s concern over many of the companies’ ability to get paid for present projects, or finance new ones if their counter-parties fall apart. The portion of midstream companies who entered this distress already stretched on their balance sheet and income statement are particularly vulnerable.

A significant tension point that lends itself again to valuing financial superiority in midstream selection but also natural gas vs. crude oil in revenue allocation is this: One of the pieces that will most serve to drive oil prices higher (what everyone seems to want for the energy sector at-large) is commitments around production cuts (Saudi, Russia, but then also likely American). Midstream assets are driven by volume, not price, so there is a fear for midstream assets that lack volume guarantees from their counter-parties that even in higher prices, the volume reduction that serves the purpose of raising prices would actually hurt them.

Capex has to be prudently managed in this period, and positive free cash flow generation is a huge premium. Where an authentic and aligned interest in returning capital to shareholders exists, better opportunities lie. We have centered our positioning in this time of distress entirely around the highest levels of quality we believe exist in the pipeline food chain. Strong distributable cash flow entering the mess is a smart way to start; but evaluating contracts, counterparty risk (total volume guarantees), and balance sheet capacity for weathering it all are additional steps that can’t be missed right now.

Occupy Levered Loans?

The government went to the wall to backstop the losses of CDO’s and CLO’s in 2008/9/10 (Collateralized Debt and Loan Obligations). I am being flooded with inquiries as to why the Fed’s facilities may not support these vehicles now (pools of debt with added leverage). The support out of the financial crisis was through injections of capital to the balance sheets of the entities that held and/or financed the debt pools (which were, at that time, the largest commercial banks and investment banks in the country – mostly household names like Lehman, Merrill, Morgan, Citi, etc.). So what is different now, as these CLO’s face varying degrees of vulnerability (depending on underwriting quality, leverage ratios, etc.)? The difference is that the systemically important institutions didn’t finance or own them – non-bank lenders did. In a cruel treatment of the English language, the question will end up being: Do the non-systemically important financial institutions represent a systemically important risk to the country’s financial system? I am not convinced the Fed will directly intervene in the CLO space, but I do suspect that if enough “domino effect” systemic risk surfaces, they will pursue a backdoor way to lend support here.

But as various life insurers and trust companies discovered post-TARP, many BDC’s and non-bank lenders (especially those who can survive margin calls without support) may rue the day the Fed deems them systemically important. There is no free lunch.

Economic forecasting and the future

I am trying to suppress my annoyance at colleagues and friends who insist on providing economic “forecasts” for GDP in the quarters ahead, knowing full-well that there are dozens upon dozens of completely unknowable variables right now that render such “forecasting” no better than astrology (someone famous said that once about all economic prognostication, but I digress). A few basic guidelines are useful in how TBG is thinking about this:

(1) I see the Fed’s interventions and the fiscal side of things very likely to keep this economic downturn from actually turning into a full-blown debt-deflation recession. It can be a lot of things, and many of them can be really bad, but a debt-deflation recession is very unlikely on the table when the Fed is looking at a $7 trillion balance sheet, and Washington D.C. is throwing $2.2 trillion at something (or more).

(2) So if we don’t go into a debt-deflation recession, what are the bigger risks (once the worst of the unemployment and suppressed consumption works its way through the system)? I would say that a structurally lower P/E ratio (multiple) is very possible with “animal spirits” contained in the economy for some time, and of course a general aura of uncertainty. But then again, that valuation story will be up against the “kitchen sink” of monetary policy, and that “push-pull” is not one I would bet against.

(3) Capital spending is assumed to be dead and gone during this recession (fair), but I am not at all convinced it will be in the immediate aftermath of the recession. To me, a larger focus on maximizing goods and services with less reliance on labor is going to be a huge priority post-recession, and there won’t be a shortage of capital for corporate America to pursue these objectives. This has economic and investment implications (industrials, etc.)

Optimism vs. Pessimism and DNA

Very candidly, I am an optimist. All I mean by that is, I believe things get better, and I focus on that improvement when things are bad because I find it a healthier way to think, live, and be than the opposite. I do not formulate my views on things getting better merely because I want them to get better; but I do like it when things get better because I try not to be an awful human being.

But let’s just say that most optimists are using “hope” as their guiding principle. Are pessimists doing something different than the inverse of that? One of the key issues that pulled me out of a worldview of pessimism over 20 years ago was the realization that perma-pessimists did not merely forecast things constantly going badly; they desperately wanted such. It was an entirely sociological and psychological phenomenon, and it was not for me.

But in my context as an investment manager, I cannot bring isolated biases of optimism to each decision, just as I am critical of the perma-pessimists who seem to lack objectivity and the gift of observation. What I have to do is provide objectivity and rationality to the decisions I make, and do so in the timelines that make sense for my clients.

And this is where optimism is not merely the by-product of hopefully being a decent human being, but also the ultimate form of rationality. What would be the empirical reason for me to function with a non-optimistic worldview? As for markets, I have lived through major market crashes, and every single one of them has rebounded violently, and gone on to make new highs in the fertile soil of free enterprise. I have lived through personal afflictions and tragedies, and every one of them has resulted in a better life, personal growth, and a resolution that exceeded my wildest imagination.

For me to evaluate the lessons of history, and conclude that this time our economy is doomed forever, that markets will never bounce back, and that the world is going to end, would not be a case of “allowing realism to overcome optimism” – it would be an irrational case of disdaining realism.

In an episode of Mad Men I have watched countless times, Lane Pryce asked Don Draper what he would tell his family (after Don fired him with cause). Don’s immortal words ring true in many contexts.

“Tell them that it didn’t work out, because it didn’t. And tell them the next thing will be better, because it always is.”

My worldview comes from the only realism I know – and I call it optimism.

Chart of the Week

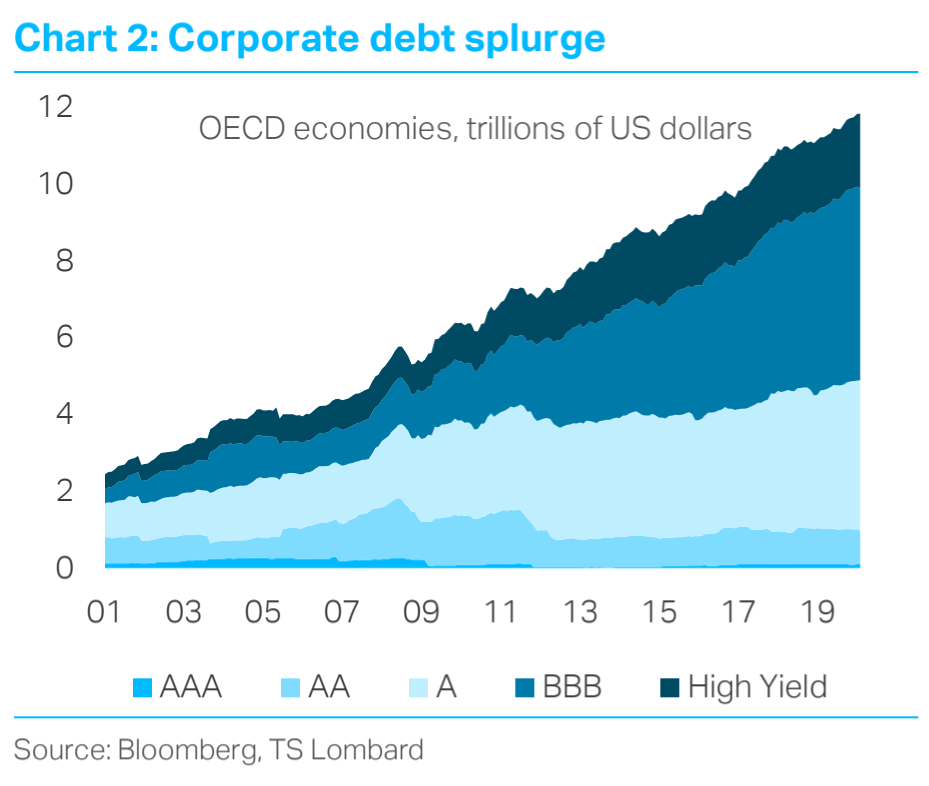

Why do I say the Fed created this monster, and now the Fed has to deal with it? The corporate leverage in the system built up in response to the reflationary objectives of the Fed post-crisis. It worked. And now with the increase in debt in the corporate economy, the Fed staying on the sidelines became a non-option.

Quote of the Week

“Apprehension, uncertainty, waiting, expectation, fear of surprise, do a patient more harm than any exertion”

~ Florence Nightingale

* * *

More Dividend Cafe coming Friday! In the meantime, the “two days down, two to go” language is really kind of silly. We have many, many years to go. We are goals-based investors. That isn’t going to change this week, or any other week. To that end, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet