Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I purposely wrote this week’s Dividend Cafe before the CPI number posted this morning at 8:30 am ET. Lots of traders were getting in front of this late Thursday, and a market that had rallied up +2,000 points in the last two weeks was down -1,000 points in the last five days and is now down a lot as markets open Friday.

We are in a period of short-term traders trying to front-run the Fed, but more particularly, trying to front-run those who they think are trying to front-run the Fed. What I mean is not as complicated as it sounds: The basic belief is that if inflation data looks worse, for longer, the Fed becomes more Volcker-like in their hawkish tightening, and that hurts risk assets; therefore, if we see a whisker of “more inflationary than expected” some will start selling, and we should sell before they sell.

Well, good luck with all that.

Today I am going to look at what could make this market get worse, not in a “traders are going to do this” kind of way, but in a real systemic, significant, macro kind of way. It will turn into a two-parter, no doubt. But let’s look behind the headlines of the day, the CPI print of the moment, and the Fed actions of next week. Let’s dive into the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

Is this market going to get worse?

A bear market is the process by which capital returns to its legitimate owner. I learned this concept early in my career from Warren Buffett and I believe it with every ounce of breath in my body. I do not believe speculators, traders, and weak hands, are the proper owners of capital. Those utilizing debt and equity markets to capture the creation of value deserve returns. Those speculating on speculators do not. Various forms of “greater fool theory” always end in pain. Except for the properly formulated investment mindset, where value creation is prized, and out of the combustion of greater fool speculation, comes great opportunity.

I do believe the excesses of the last several years are severe enough that this can get much worse.

To take this lower you need a mega-collapse – a re-defining moment – what people call a “black swan.” What could that be?

European bonds

These have been a popular culprit as the next debacle waiting to happen for the last decade (actually, for 12 years now). Maybe things will circle back around here, but all indications are that the bazooka of Draghi kept this asset class alive, all the while creating other challenges that are for another discussion. Would a systemic crisis in European debt create a global recession, and therefore a new leg down into a major bear market? You bet. But is that likely to happen here now? No, it is not.

Crypto

Is this the new catalyst for dogs and cats falling from the sky? After all, over $1.5 trillion of value has been wiped away in the last few months, and there is no reason to think the price carnage could not get much worse. I still believe the potential is there for this to get much worse, but I hesitate to view it as systemic. It is still a small part of the population who owns it, there is no banking system leverage tied to its ownership, and I basically view it more like dotcom than a broader market exposure – meaning, those who speculated in it hold the risk; not the entire society. If anything, I think moving past the silliness of the last two years might be, in the long-term, healthy in putting people back to work, etc. I think this is not going to end well, but I do not see it as something that brings the whole risk asset world down another notch.

A mass municipal failure

Well, this can never be discounted, because indeed there are city, state, and county finances indebted to their eyeballs. And the expected decline in sales tax, property tax, and state income tax at the beginning of COVID was cause for grave concern. But the federal government took on all that risk, rained money on these municipalities, and flushed them with cash in a way that is truly obnoxious for anyone paying attention to the cash receipts of these states. These are not the best stewards of capital God ever let walk through the door, okay, and they probably don’t deserve their checkbooks. But imminent bond collapse? No.

Even with high profiled municipal problems in Detroit and Chicago over the years, the muni market has simply never come close to creating the systemic panic and problems that its critics have understandably forecasted. Can-kicking? Yes. Pension obligation gamesmanship? You bet. But a federal backstop on top of taxing authority on top of a basic ability to continually roll debt? That’s been the winning bet here for a long time

Some hedge fund we don’t know about

Long Term Capital Management in 1998. Archegos in 2021. Someone out there with some leveraged play that no one is following. After all, over-indebtedness always is the cause of bear markets and deep recessions. But the failure that comes from insolvency must be systemic for it to be recessionary. When it is isolated to the risk-taking actor alone, someone destroys capital, but it simply is not systemic. Someone gets poorer, but it simply is not recessionary.

If one believes the world faced a true crisis from Long Term Capital in 1998, it would not be because of the losses in that hedge fund or losses its investors faced. It would be because of the losses the banks backing the fund took. I understand the press to some degree, and politicians to some degree, want to paint Archegos last year as a new Long Term Capital type story, but that is because people are either lying through their teeth, or have no idea what they are talking about. Some serious capital got destroyed by the busted trades of Archegos, and some mega-rich people became not mega-rich. And all I can say is, that has nothing to do with you or me – nothing. Isolated capital losses that do not bleed into the financial markets at scale are not systemic. Risk-takers lose money all the time, and while the sheer audacity of these leveraged plays at Archegos make for exciting journalism, they are not even close to being systemic events, and in fact, did not even involve outside investors. Some may care about the story and some may not, but no one actually believes it threatened financial stability. No one.

And this brings us to today’s nominee for the next driver of market pain and destruction

Private equity, non-bank lenders, private credit, and overall leveraged finance in the private markets

We have seen an explosion of transactions in the private markets, both in the quantity of deals being done, the quantity of borrowed dollars supporting these private deals, and the complexity and scale of financing activities involved in all of this. And unlike the mortgage/housing debacle of two decades ago, these activities are not on the balance sheets of your household bank. They are in a “non-bank” cottage industry that now spreads all over American and global finance. And I am totally willing to discuss the possibility of this space becoming the catalyst for a new black swan event …

Eyebrows raised on private equity?

A certain argument against private equity investing caught my eye this week, but not for the compelling nature of its case against private equity. Rather, it forced me to think deeper about some of the stuff I (we) read …

The gist of this private equity critic’s argument was that:

“In the year 2000, the average leveraged buyout was done at a 50% discount to the S&P 500.”

“In 2021, the average buyout was done at a 10% premium to the S&P 500. And this is when S&P valuations themselves were quite high!”

“Leverage levels and credit quality is worse than ever.”

“Therefore, the private equity, leveraged buyout space is in real trouble!”

So what caught my attention? Well, not just that some of the “facts” are untrue, but rather, how the “facts” are come up with at all! And then this got me thinking – how many times are things said like this, pulled out of a hat, possibly made up out of thin air, and best case, totally decontextualized and mispresented, yet still passed over as action-generating facts? I think it happens a lot.

So what are the problems here?

How does this person know that the average leveraged buyout was done at a 50% discount to the S&P 500 in the year 2000? What public (or private) information is one using to calculate this? I can tell you because I know, that:

(a) There were a fraction of the leveraged buyouts in 2000 in private markets that there are now

(b) They were hyper-private, unknown, undisclosed, and non-reportable. Therefore, “indexing” them is, well, nonsense.

(c) What multiple is he using on the S&P to say deals were done at half of the S&P? The 29x it started the year at, meaning, 14-15x, or the multiple it ended the year at (or somewhere in between)? Not only is this not true, but it is unhelpful even if the basis sentence were true since the reference point itself is massively wide, vague, and unsubstantiated.

Okay, so the first premise towards the conclusion is just completely useless and fictitious, but then there is the second premise, that the average private transaction in 2021 was done at a 10% premium to the public market. Well, the S&P traded at 22x FORWARD earnings last year, and 26x BACKWARD earnings. So is this person suggesting that the AVERAGE PRIVATE EQUITY BUYOUT was done at somewhere around 25-30x earnings? And since PE transactions are generally valued at a trailing-earnings stream? Does anyone actually believe that? Because if so, I have a bridge to sell you somewhere.

What about the third premise? Are leverage levels and credit quality worse than ever? What if I said to you, “food is worse than ever.” The “quality of nutrition is worse than ever.” Have I said something about all grocery stores, all restaurants, all farms, all diets, all anything? Are we to believe that the fateful and famous 1988 LBO of RJR Nabisco (Barbarians at the Gate remains the greatest business story real life as narrative book I have ever, ever read) was “the good old days” compared to today’s valuations? (Hint: it was one of the most capital destructive transactions on record). The fact of the matter is, there are a lot of good deals being done now and a lot of bad deals, and in “the good old days” there were a lot of good deals and a lot of bad deals.

So there are deep and factual problems in all three of the above premises, therefore the conclusion should be taken as one formed out of three deeply and factually flawed premises.

What is really being missed?

What bothers me most in analysis like the above is that I believe there is something to critique in the present state of credit markets, leveraged finance, capital structure, and private markets; and pedestrian, truth-lacking, ignorant analysis detracts from the intelligent critique that is needed.

First of all, one has to understand the difference between deals being done when the cost of debt is 4 to 8% vs. deals being done where the cost was 12 to 20%. Now, the immediate reflex may be to say, “oh yeah! Debt costs a lot less now so that is better, and makes it easier for companies to service the cost of debt.” Well, true enough, in theory. As math goes, borrowing at 5% is indeed a lower interest expense than borrowing the same amount at 15%. But, one isn’t likely borrowing the same amount, because the lower interest expense means the deal can have more debt in it. In other words, the price of debt influences the price of the deal. And so there exists a price signal that gets distorted by the cost of capital. A company that may be worth X transacts at something more than X because the low cost of capital enabled it in a spreadsheet. And the problem here is that X does not ultimately and fundamentally become Y because of a spreadsheet. X = X. And so a mal-investment was made, because of bad information – bad price discovery. And this is not good.

Now, some of these deals work out. In fact, most do. Timing works in their favor. They do some good things, turn some knobs, and exit the position before tides drop. But at the end of the day, transactions happening with a broken scale are dangerous, and disciplined buyers care about value – not finding a greater fool to sell to.

My Conclusion is different than theirs

This is the point I am making: In a period of a broken scale, risks are elevated, but the opportunities of enterprise are not; they just require more diligence.

I would argue that valuation concerns in private markets, questions about leverage, and the broad/wide/deep questions about distortions in markets that interventionist monetary policy has created argue even more for high-quality managers, good underwriters, and proven stewards of capital.

Lips moving

But before we can unpack who is a good private equity manager and who is not, or what deals do make sense strategically and financially, and which ones do not, and where systemic risks exist in the system, or do not, we first must point out a truly difficult reality also altering the scale by which we look at things: Some of the information one reads to make their decisions or form their opinions is really bad information.

There are two different things going on here, but I am only referring to one of them. One is the easy part I have already addressed: Accurate premises that lead to different conclusions. No problem. Life is supposed to work this way. Mr. Smith and Mr. Jones both acknowledge the challenges of a prolonged period of easy credit, and Smith decides to avoid anything altered by such a distortion, while Jones decides to proceed with caution, diligence, and specialization. One can be right and one can be wrong, but everyone is on the same page about the landscape of easy credit.

But the second is the bigger problem. Just utter nonsense passed on as fact. “Deals were at a 50% discount and now are at a 10% premium.” I mean, come on. How is anyone supposed to respond to this dictum? Well, hopefully, they respond by deleting it.

So what are you saying?

Some private equity deals done in the last few years and in the next few years are going to make really, really good returns.

And some private equity deals done in the last few years and in the next few years are going to lose a lot of money.

This is not a monolithic space. I believe one should be very prudent in their investment allocations here, and I believe a deep recession here would hurt the operating businesses involved, but that is a tautology. It is true because that is what a recession is – a period where operating businesses suffer.

The question is what may or may not be systemic.

Next week

And that brings me to the subject of leveraged finance in general, even outside of private equity (the leverage put on deals to finance equity transactions). I may not feel the need to make up statistics to rationalize a false narrative about private equity’s systemic risk, but that doesn’t mean I do not have concerns about leveraged finance in general. Next week I will start a deeper dive into other elements of credit and debt reality that warrant further reflection.

In the meantime, avoid the liars and charlatans that feed you bad information. And avoid investing without a good scale. Diligence is key. To that end, we work.

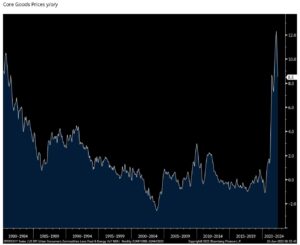

Chart of the Week

The CPI report came in higher than expected, with Services leading the way. But for the third month in a row, the rate of inflation for Goods came down (our call was that this had peaked two months ago). It is still at such a high inflation growth level that it isn’t being discussed, but the disinflationary direction of core goods will be the major story in the inflation narrative for the second half of 2022.

*Bloomberg, Boock Report, June 10, 2022

Quote of the Week

“Never lend money to somebody who needs it.”

~ Ernest Gutzwiller

* * *

I am excited to continue this subject next week and look deeper into the non-bank financial system. Private equity may not be the culprit (it is, in fact, my contention that it is not). But there are other layers of leverage and credit and complex finance that warrant unpacking.

In the meantime, reach out with questions/comments, and take nothing from pundits or press at face value. Trust comes from trustworthiness. To that end, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet