Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

It’s been a whirlwind of a week, and today is going to be a whirlwind of a Dividend Cafe. I came into my writing this morning with two or three topics to choose between, and I settled on “all of the above, plus several more.” I’ll leave the introduction short so we can get right into it. Between earnings season, a certain crux in the geopolitical moment, potential (likely?) new tax legislation, a modest market re-pricing of revised Fed expectations, some company considerations in our own portfolio management, and a pleading of the case for a “full-time” work mentality, there has been a lot going on at Team Bahnsen, and there is a lot in today’s Dividend Cafe … Let’s jump in!

|

Subscribe on |

Did someone say “full-time”?

I have had several people (clients and non-clients alike) ask why I would write a book arguing for a more robust thinking and practice of work when I am an investment and economic guy. Indeed, my new book delves outside my normal lanes in a couple of ways, pleading for a different approach to work (that is, a more favorable one) sociologically, ecclesiastically, theologically, and personally. In what sense is this message pertinent to my focus on economics?

“Work’ is the verb of economics. In the study of economics, we deal with human beings, made a particular way to do particular things, who are “burdened” by the reality of scarcity. Unlimited resources change economics. Scarce resources force upon us an “economic way of thinking.” In addressing scarcity while seeking provision and betterment, a market economy made it possible to enhance our own quality of life while the quality of life of everyone else was enhanced. Goods and services can be produced as a by-product of addressing scarcity, and in the miracle of a division of labor and work specialization, dreams can come true. Passions and skills can be married. People can have a better life. And they can only do this if they are serving their neighbor – that is, making goods and services that meet the needs and wants of others (and in most cases, the “others” here are not merely the person next door to them, but potentially millions of people around the world they have never met). In this incredibly complex and multi-layered reality whereby social cooperation is fostered through exchange, the need for capital to create more means of production exists, and the return on that investment rewards those who invest in the equity or debt of these opportunities (subject to the risks that are inherent in such a system). The returns from those investments are used to facilitate the needs and wants of the risk-takers who made the investments, and those investments themselves facilitated the needs and wants of the underlying customers of the business.

Now, re-read the prior ten sentences or so that make up the preceding paragraph. Find one sentence that doesn’t require work – that doesn’t presuppose work – that doesn’t involve work – that doesn’t take work for granted. Find one sentence describing this entire cycle of modern economics which isn’t itself a sentence about work.

I have written a book about work because work is the verb that drives all economic activity. It is what we were made for. It gives us purpose, it honors our God-given dignity, and yes, it is the sine qua non of all economics.

So yes, I care about work. Because I care about the person doing the work, the person being served by the work, and I care about you investors who are actually investing in a process of work, even if you aren’t accustomed to thinking about it that way.

A Modern Portfolio

A fascinating thing to observe is how a 60-40 portfolio (generic term for a generic portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds) became synonymous with “modern portfolio theory.” As a basic construct, the great work of Harry Markowitz in developing what we call modern portfolio theory was nothing more than the incontestable facts that:

- Investors prefer maximum returns adjusted for the risk they take to get them.

- Such risk is diminished (but not eliminated) through diversification.

- Different asset classes can be combined based on their own historical returns and historical mean-variance (standard deviation) that reflect historically optimal blends of risk-adjusted returns.

It cannot be prophetic because, you know, I just used the word “historical” like five times. But the theory never made dogma of history; it referred to an optimal aspiration in a portfolio – the incontestable fact that if two portfolios have the same return over time, investors will always want the one that gets there with less risk and volatility.

So, count me as an adherent – I agree with basic incontestable facts of reality.

But what does this have to do with 60/40? Why did the industry assume that a 60% stock and 40% bond portfolio were one and the same with MPT? The combination of the two asset classes performed very well over a long period, especially when the 40% portion (bonds) watched a long bond go from an 18% yield to a 2% yield (math). And yes, because of the stock market mean-variance, the risk-adjusted return of a 60/40 portfolio when the 40% portion is performing well will be very good. 1980s and 90s, mission accomplished.

But nothing in modern portfolio theory, nothing, speaks to what is being done with the equity component or why the weightings should be universal for different people of different ages and stages, different liquidity and risk profiles, and different objectives in terms of return, timeline, growth, and income. Furthermore, nothing about MPT presupposes only two prominent asset classes. If mean-variance optimization and blending of non-correlated asset classes speaks to investor aspirations for superior risk-adjusted returns, the inclusion of diversifiers is perfectly compatible with MPT (i.e., hedge funds, private equity, real estate, private credit, global macro, etc. Out of this revelation (thank you, John Mauldin and Alexander Ineichen, the two men who helped form my thinking on this subject over 20 years ago) came our belief in including alternatives in a client portfolio towards the aim of optimizing the journey.

Now, it is not enough to say that a portfolio’s historical returns and variations with alternatives will be superior to one without, even if that is our position at a macro level (i.e., using generic assumptions about generic asset classes). Alternatives are not “beta” asset classes – they are not “indexable” – they are, themselves, by definition, inherently idiosyncratic. So, selection matters. Execution matters. And that scares a lot of people off.

We embrace it.

1999 was a great year

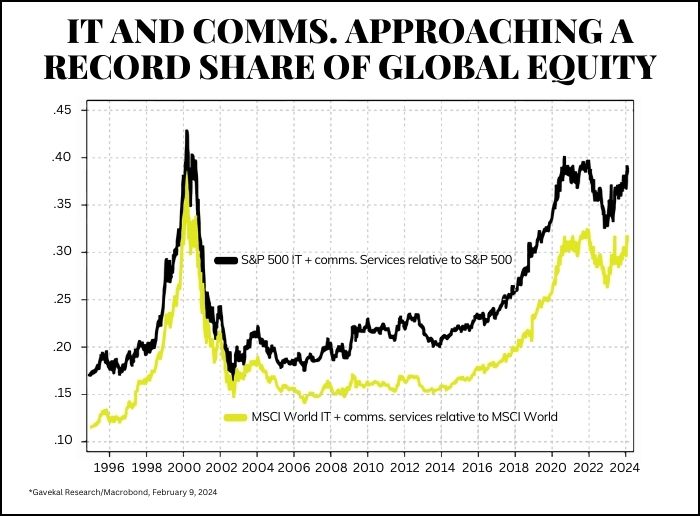

I have made plenty of comparisons to the current moment in AI and much of big tech to the 1999 boom (which was really a 1995-1999 boom). The Fed was quite involved, and the general valuation levels and cultural context were eerily similar.

But of course, no one minded in 1999. And you could argue that 25 years later, no one minds. If they were diversified, if they adjusted, and especially if they took a nap for many, many years along the way of the last 25 years, perhaps it all feels like a happy ending.

I will just say that one thing that is materially more painful than not participating in a bubble is participating in a bubble burst. And yet, these terms and descriptions are nearly worthless as forward-looking vocabulary because we do not know a bubble has burst until it does. Along the way, we are all just exposed to the possibility of looking like chicken little.

What I can do is use history to my advantage. What tips us off to a bubble besides astronomical valuations (check), Super Bowl commercials (check), and future B-team celebrities that are currently A-team celebrities selling their soul to be in a commercial?

I would suggest that this week’s Chart of the Week is useful. I would suggest that 72% of the stocks in the S&P 500 last year underperforming the S&P 500 is useful.

So far, it is just Chinese tech stocks, Electric Vehicle stocks (dear Lord, has anyone noticed what has happened there?), and, of course, the “low quality” tech graveyard of 2022 that has gone the way of the early 2000s. That graveyard is grotesque but does not yet include the mega-cap names that have become the darlings once again. Cash flows and profitability are better than the big-cap names of 1999. Maybe this time, it’s different? Maybe a phone device company with seemingly unlimited applications in services and software can become more valuable than the entire market cap of the WORLD!!!!!!!!!!

But maybe, just maybe, history is a powerful teacher. And the future belongs to those who learn its lessons.

Chart of the Week

Quote of the Week

“If you’re not willing to do more than you’re being paid for you’ll never be paid for more than you’re doing.”

~ Unknown

* * *

I will be in Florida next week, but not for a single minute of vacation. It will certainly be filled with enjoyment, though, because I enjoy working more than vacationing. It’s called the economic way of thinking.

Have a wonderful weekend, and go, Taylor Swift. In many ways, she already won the Super Bowl.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet