Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Four weeks ago, I devoted a Dividend Cafe to the subject of a “dividend growth mentality.” It was intended to, amongst other things, reiterate much of the underlying value proposition for investors in buying companies that return capital to shareholders via dividends and who increase those dividend payments year-over-year. The people who read Dividend Cafe are mostly investors, and all clients of our firm are investors. My interest in dividend growth is investor-centric – that is, how dividend growth accrues to the benefit of our clients.

And yet, as became clear to me from a couple of letter-writers in the aftermath of that Dividend Cafe, there is a sense which it begs the question to ask why it is good for investors to receive dividends. Don’t we first need to understand why companies, themselves, pay dividends? Would the benefit to us as investors matter if there were no benefits to the companies? Or is this whole thinking sort of confused?

Well, one thing I can promise you – you won’t be confused on any of this after you jump into this week’s Dividend Cafe, where we will seek to unpack this whole subject of companies paying dividends – why they do it, should they do it, and what does it all mean (economically and even philosophically).

Let’s be honest; this is about as fun as it gets. So join me in the Dividend Cafe.

|

Subscribe on |

All the questions fit for print

Why do companies pay dividends? Perhaps a better question may be, why do some companies not pay dividends? Would the latter question help us understand the superiority or inferiority of those who do? Do companies only pay dividends to altruistically “thank” their shareholders, or is it beneficial to the company? Are dividends just a means of juicing up the price of a stock? And while we are on that subject, why do companies care about the value of their stock? How should we think about a company’s decision to weigh a dividend payment vs. retention of profits for future growth? Just a few things to bite off in this week’s Dividend Cafe …

(H/T to Todd C. and Kevin G. for two thoughtful letters sent independently of one another)

The first question to ask

I think we likely end up in the wrong place if we start by asking why companies pay dividends. It benefits us if we are going to go back to basics to really go back to basics. The sort of existential reality of a business, the investors who gave it capital, and the fundamental things going on there are all helpful to keep in mind as we unpack the more layered elements of dividend purpose. First and foremost, the company is there to generate a profit, and the only way it can generate a profit is by delivering goods and/or services to people who benefit from them. A company exists around some ability, brand, product, service, and function within the marketplace that has value. If it doesn’t, it will not likely be a “going concern” for long.

In order for company A to be in a position to sell their ABC products or XYZ services to the marketplace, most companies need capital. It is expensive to market, to build out sales and distribution, to produce a product, to hire talent, and to do the research and development necessary to have a good ABC product or XYZ service. That capital, when it takes the form of equity (ownership) versus debt, has risk associated with it. In fact, the investors can lose all they invested if the company does not make it. And their only gain on investment will be if the company (a) Survives (duh!) and (b) Becomes more valuable. Profits (or the continued belief in a future of profits) are the only ways ever concocted to become more valuable.

So before we ever think about a dividend as a way of monetizing an investment, we really need to think about the basic setup of all this:

(1) Before there is a dividend, there has to be a profit. It is profits that businesses are after – the creation of value from the endeavors of a business (the delivery of goods and services that meet the needs and wants of humanity). Period. That is it. If you can remember this elementary foundational truism, you will quite possibly be more qualified to teach economics than half of those who occupy the faculty lounges of our universities today.

(2) When we talk about why companies pay dividends, we are merely talking about what they do with profits. If a company does not have profits or a path to profits, it will not be a company for very long. But in the world of dividend growth (and much of public equity companies), we are talking about profitable companies.

So by definition, this conversation is not about why venture capital companies do or don’t pay dividends, or why start-up companies do or don’t, or why private companies in a key growth stage do or don’t. Dividend growth companies start in the universe of “mature” businesses already in a position of “steady profits” – that is, their business endeavor has afforded them the ability to reliably sell ABC products or XYZ services at a good profit margin. They long ago met the first burden – to produce goods or services profitably that meet the needs of humanity.

Now we are just talking about what to do with those profits.

Mattress money as an option

Dividend payments are a form of return of capital to shareholders. The question has been posed, “Why would the company return any capital to shareholders?” Why not just hold on to it? Is it just to be nice to shareholders (that is, maybe a bad thing to do for the company, but an act of gratitude and goodwill)? Is it to “juice” the stock price so that the company benefits from having a higher stock price? Or is there something else going on?

Well, let’s remember the presupposition before we consider a dividend payment. There first has to have been profits. So the company is sitting on some earnings. In our universe of companies and category of contemplation, they are repeatable and sizable earnings from a mature company. So, what could the company possibly do outside of paying a dividend?

One option is they could do nothing. The profits could just sit there in a company bank account, just as they could sit in the bank accounts of the owners of the business (shareholders). In this case, the company has more cash on hand, but its return on equity goes down if the amount the company earns with cash sitting in the bank is less than it generates from its actual business enterprise. Any time the company is earning less than its cost of capital by sitting on cash, they are eroding value.

This is very important. A company with a good return on equity is efficient at generating profits with its equity (that is, the assets of the business minus its liabilities). This is sort of table stakes for good public companies – we do not need to do an IPO for a company whose business model is “holding cash in a bank account.” All of us can open bank accounts on our own. All of us can buy “boring bonds” on our own. A company exists to profitably deliver goods and services that meet the needs of humanity. So a higher return on equity comes from the enterprise than from holding cash in a bank, or else holding cash in a bank is a better investment than the equity of that company.

If you can put $100 in a bank account and make $3 per year in interest, or you could put $100 into a lemonade stand and see $1 of profits generated per year, you’d skip out on the lemonade stand investment. But if you could make $10 per year from the $100 investment in a lemonade stand, you then consider that investment versus money in your bank account (“consider,” because you still have to think about risk, liquidity, etc.).

So once we take for granted that the companies in the universe we are discussing do better generating returns from their enterprising activity than they do with cash in the bank, we establish the principle of “opportunity cost.” There is a cost to letting too much money sit in the bank, and companies are wise to try to productively deploy as much of their cash as possible in their profitable endeavor.

So cash sitting in the bank for no reason, earning less than the company’s cost of capital, is a bad idea.

Business growth meets a law of economics

Another option is that the cash can be used to reinvest in the business. And, of course, this is what I am after. I do not want dividends at the cost of the company doing more of what it does that generates the profits that generate the dividends! Read that sentence again, please. Dividend growth that cuts off the source of the dividends is silly. But this whole thing begs the question, as well. There is a law of marginal utility in economics, and at some point, the company does not need more cash for more delivery of ABC products or XYZ services or stated better; there becomes a diminishing return. If I will have 1,000 people walk by the street corner my lemonade stand is on this weekend, I can spend more and more capital to capture that street corner’s market share, to upsell customers, to glitz up my marketing, and so forth and so on, and maybe one person spends $1,000 to prep for that weekend’s opportunity, and another spends $2,000, but I think we can all agree that spending $1 million might be a bit excessive. Paying $1 for costs to sell one glass of lemonade for $5 warrants plenty of $1 investments, but at a certain level, the opportunity diminishes.

And so it is with all businesses.

Reinvestment is a given. A mature public company with repeatable and strong profits owes it to us to reinvest an adequate percentage of those profits into capital expenditures needed to run and grow the business. But that number is often not 100% of profits, and it better not be 100% in perpetuity or else you don’t have a business – you either have a Ponzi scheme or you have a zombie business!

And I should point something else out as well. This is also where capital structure matters a lot. I have learned more from Michael Milken about this subject over the last 25 years than anyone else. For large and complex businesses, the savvy in how debt and equity and various conventions of capital markets are used to optimize a company’s capital needs is a vital skill in our complex economy. Would a company making a billion dollars of profits selling XYZ that stands to generate two billion dollars of profit if they make another round of XYZ widgets do better by raising debt (the interest payments of which are tax-deductible) or by using the profits to fund this expansion? It isn’t always simple – there are risk issues and concerns across a large and complex business – but often times the use of profits to fund expansion versus reasonably and responsibly tapping the debt markets can be a very bad idea.

Of course, excessively tapping the debt markets instead of using company profits can also be very irresponsible. Each situation has different particulars that matter a lot. The cost of debt is one part of the cost of capital, just as the cost of equity is. This was Milken’s teaching – recognizing the wisdom of capital structure in evaluating a company.

Some companies are more capital-intensive than others (think telecom, industrials, energy, etc.). Some companies need very little outside capital to fund expansion (this was sort of the value proposition of many tech companies over the last 25 years – that they were capital-light yet with high-profit capacity).

Bottom line: companies should use profits to reinvest in the business up to the point that the law of marginal utility makes sense for them to do so, and yet not past the point at which they erode the value of their business with diminishing returns (lemonade stand example above).

When teenagers run the asylum

A third option is that companies say they are holding on to cash for business expansion, but really they are setting money on fire. This means they become wasteful, sloppy, arrogant, and unwise. Costs balloon. Bad deals get done. Management becomes less efficient. Management becomes lazy. Excess cash breeds poor performance. It. Happens. All. The. Time.

Let me ask you a question. Instead of directing to ABC Super Large Corporation or XYZ Big Deal Business, let’s ask Mr. and Mrs. Smith. Have you ever found that cash deployed from your checking account to your savings, or stock portfolio, or house renovation, or new real estate gets deployed well, whereas cash left in your checking account gets spent on more online shopping, Taylor Swift concert tickets, or an insufferable collection of expensive ties and cufflinks? Why would a business be any different than a household? Human nature is immutable. Businesses waste money when it is not deployed wisely.

This is not merely about incentives. Excess cash breeds complacency. The testimony of history is abundantly clear. One can say all day that the company management is incentivized not to let that happen, but the incentive differentials between management and ownership are an important part of this conversation (more on this below). A company’s board of directors often picks capital return strategies (like dividends) because the alternatives include the company’s managers spending too much money, taking bad risks, and, the mother of them all, poorly thought-through mergers and acquisitions.

“Giving back” rightly understood

If there is ever a time that the phrase “giving back” is used correctly, it is when we talk about a company returning capital to shareholders. In that case, an investor really did give capital to an enterprise, and when they receive profits from that investment, the company is “giving them back” their money (along with whatever return on that investment it generated – a coupon payment for a bondholder, or a share of profits for a stockholder, etc.).

(I fully understand the semantics of “giving back” when it is used in a charitable or philanthropic context, but I do not like it. The donor is not “giving back” to his community or museum or church unless he first took the money from them – he or she is just “giving” – and I am all for it, and I love generosity and believe in it tooth and nail, but it is not “giving back” – and if it were, it wouldn’t exactly be “generous,” now would it?).

Okay. Back to the point at hand. Capital return is “giving back” to the owners of the business the capital they invested, along with the return generated. So our question at hand is, “Why would a company pay dividends to its owners?”

My answer has been that the other alternatives are bad for the company, and we already know they are bad for the investors.

#1 – hoard cash that depletes the value of the business (it is generating less return than its cost of capital).

#2 – hold cash to put back into the business (good), but then hold more cash than is needed for such (bad)

#3 – waste cash with frivolous spending and deals (it gets management fired and depletes the value of what they own in the company)

And it is that last point that is important. When one asks, “Why should the company pay out dividends to shareholders?” are we sure we understand who the company is? Today in American public equity that answer has changed a lot.

Skin in the game

For all of the controversy around Gordon Gekko’s famous “Greed is good” speech, the irony is that the entirety of that speech was a work of art besides that flawed Randian line. His whole speech was about the low level of ownership that management had in the businesses they ran (in public markets). Take out the “greed is good” line (because, sin), and the speech was magnificent.

One of the real challenges with public equity ownership is that management often has so little skin in the game. We want management aligned with shareholders for this very agency problem. Technically, you can run into public company situations where the incentive of management is to hoard cash, throw parties, spend lots of money, do M&A deals, and everything but pay dividends. That can happen. But you can imagine what I might say about that. “We would, ummmm, not like to invest in those companies.” One way to solve for the agency problem has been to tie a lot of executive compensation to the stock. I like it, but it isn’t perfect. Stock options, stock grants, and restricted units are all ways to give management ownership in the business, but they are one-directional. They give management a lot of gains if things go well, but their own balance sheets and actual risk capital (from before they joined the company) do not hurt if things go poorly. I love love, love businesses where management owns a lot of the stock – often founder-led companies – that have actual capital deployed in the business (sometimes their own capital). A second best option is when management spends a lot of their own money to buy stock in the company they are hired to run. That happens, too, but not enough. The third best option is alignment through the executive compensation of stock ownership.

So yes, in all three of the above scenarios, management has some incentive to do what is best for value creation. And value creation is optimized with the wise blending of:

(1) Profit redeployment into future growth, with

(2) Proper reserves and balance sheet strength for future needs, and

(3) Then, a return of capital to shareholders

Investors invest for return. If they do not receive it, they do not invest. Management is not the company. They work for the company. A board is hired to steward these things on behalf of the owners of the business, and that board may be good at what they do or dumber than a box of rocks, but when one asks why the “company” pays a dividend, the company is its owners.

Conclusion

Investors own a company and hire a board to steward its affairs, and that board hires management to run the day-to-day. Sometimes that management includes founders and legacy leaders, and sometimes it does not. But professional managers of a business are not the business; they work for the business. The business has owners who deployed capital for the sake of a return. That return is enhanced when there is adequate safety in the balance sheet to weather bad times. That return is enhanced when the company has adequate resources to invest in needed and useful expansion. And that return is enhanced when a company returns capital to its shareholders rather than hoard it, waste it, and otherwise have it earn less than its own cost of capital.

When a company’s management, board, and investors all see these things the same way, you have alignment.

And if I believe (as I do) that human flourishing is enhanced by the creation of goods and services that meet the needs of humanity, well, I really believe that human flourishing is enhanced when company management sees doing this as a predicate to returning profits to shareholders.

Heck, if enough companies do this well, you might just see more companies want to do it, as more investors want to receive it. I mean, call me crazy, but maybe, just maybe, the reality of incentives might create a virtuous cycle where the production of goods and services is creating dividends, and those dividends are incentivizing capital investment for the production of goods and services.

It’s a dreamy scenario.

Chart of the Week

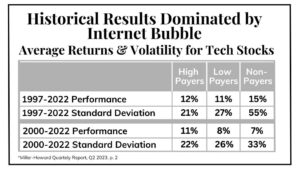

Before one gets too sure that the technology sector bucks the trend of the efficacy of dividend payments to shareholders, one may benefit from the facts of history that include all comers, not just exceptional exceptions.

Quote of the Week

“When arguing with a fool, first make sure the other person isn’t doing the same thing.”

— Old Proverb

* * *

I hope this has been as fun for you to read as it was for me to write. Next week – Chinafication. I already can’t wait to write it. To this end, we work. Have a wonderful weekend.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet