Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

It is appropriate and perhaps entirely ironic that the subject of this week’s Dividend Cafe comes in a week where we have seen some of the most bizarre, insane, and silly market activity, ever, and that this bizarre, insane, and silly activity is accompanied by totally incoherent commentary from various pundits, politicians, and “pros.”

Whoever said investing was all math and science is an idiot.

But the drama of this week’s market, and even the circumstances around the big headline story of the week (which has actually morphed into a multi-faceted story), really do serve as a reinforcement of the major principles, beliefs, and applications I want to highlight in this week’s commentary. I began writing this Dividend Cafe last weekend, and had conceptualized my thesis well before the drama hit the tape into the week. And I haven’t altered that thesis or even the way I unpack it at all. To the extent, some of this week’s Dividend Cafe connects dots with other news stories, great. But my purpose in this week’s commentary is not to make sense of a four-day story but a four-decade story.

And I really hope it will help you in your journey and understanding as an investor.

I have long believed that all professional investors are irreversibly shaped by the era in which they grew up as an investor. This is more true of the lessons learned in that era that proved to be negative lessons than positive ones. Put differently, the major events that damage us in our formative years teach lessons that don’t go away easily.

I want to do a little history this week, talk a little investment biography, and ultimately, offer some lessons about my outlook on the present investing era that ought to transcend anything you will find in a chat room, on social media, or in the madness of the moment.

It’s a low bar.

You are what you eat live through as an investor

I did not grow up as an investor in the early 1970’s when the “nifty fifty” blew up after years and years of no price being too high and a sort of invincibility to these dominant names. But had that been my formative era, I would never again believe in the “nothing bad can happen” thesis that used to circle around blue-chip names. I was born as that era was in the midst of its combustion, and while I have studied it immensely, I was too worried about USC-Notre Dame in 1974 (we won) to worry about the Nifty Fifty.

I did not grow up as an investor in the years that followed where high commodity prices ruled the day, high inflation meant high bond yields, and low P/E ratios were embedded into stocks. I imagine the tough economics of that era impacted my family, but my dad was a doctoral student at USC and later a professor; commodity prices were the least of our family’s financial concerns. Plus, I was a little kid, and I wouldn’t have appreciated the moment if I had understood it. But how that era fostered a generation of incorrigible gold bugs is not at all a mystery to me, even if I do consider it a tragedy.

I also did not grow up as an investor in the M&A craze, animal spirits, re-leveraging, high yield, growth boom of the 1980s. I also have studied this era obsessively, and I frankly wish this era had been my introduction to capital markets. Those investors cutting their teeth in this era could be so event-driven in their mindset is perfectly understandable, and how credit became a leading factor in understanding all capital markets, including equity, is entirely logical post-1981-1988. Formative times out of the old Solomon Brothers and Drexel Burnham world that permanently influenced a generation of investors.

Along comes the 1990’s

The second half of the 1990s represented an entirely new era as it is the time we most often connect with the “technology boom.” That would be news to companies like Apple and Microsoft, which actually were up and comers out of the late 1970s and into the early 1980s. And it would be news to anyone in Silicon Valley (or Texas, for that matter) throughout the 10-15 years preceding the dotcom era, as technology was absolutely re-shaping the American economy well before 1996 and Netscape’s introduction of the web browser to an IPO craze. But what was unique in the later 1990s was a multi-year tolerance from financial markets of unknown technology companies that had questionable outlooks, risky projections, and little or no track record, assets, cash flows, or management teams, to fall back on.

In other words, tech had become the driving force of American growth well before the late 1990s, but it had still had to play by the rules (i.e., “make money” and “don’t lose money” and “be smart” and “only throw wild parties if you make money”). The rules changed from about 1996-2000, and this was the era in which I became an investor.

The lesson I took from the era was not its heyday, but its ending. I have much more to say about all of this.

Don’t forget the house flipping

I do know people who the only thing they know of “investing” was flipping homes from 2002-2006. The idea of ever doing anything but buying a home with as much debt on it as possible, putting a bit of lipstick on it, then selling it for some “easy” profit is incomprehensible to them. It was all so easy. And yes, one would think 2007-2009 blew that reality out of the water. But not really. The human nature in it all is pretty hard to remove (“I can make a lot of money, pretty easily, and mostly with someone else’s money driving it”). Plus, the majority of the losses from that era’s spectacular implosion were not borne by the “investor” but by the lenders (textbook moral hazard). And since the low cost of capital that fed this mania came right back on the other side of the financial crisis, the “lipstick on a house” investment thesis is still well-engrained from folks who are by-products of that 2002-2006 era.

This brings me to the FAANG era

Most of the people I work with professionally were investors before 2014, let alone before 2017 and 2018. In fact, TBG works with some clients that were rather well-heeled investors even before the 1970-1974 era that I used to start this history lesson. But there are plenty of investors who will forever and ever know these last 5-7 years as their introduction to investing – their formative introduction. This has been a period where a very small number of companies became very, very large companies, led by their deserved distinction and prominence as technology leaders and innovators. They enjoyed mind-boggling returns, which fed on themselves as it coincided with a period of multi-trillion dollar growth in the passive index industry that became a source of forced buying, in proportion to the size of the company (cap-weighted indexes)! These incredible money flows (technically) coupled with extraordinary company success in innovation to fertilize an investment era – large, monopolistic tech behemoths that have led markets.

Note what I am saying, not what I am not saying

I do not have anything critical to say about any of these eras. They are not good or bad, per se; they just were. And that people – especially professional investors like myself – become largely defined by the era in which we “grew up” is not a criticism – it is a neutral statement of fact.

Our formative era helps create experiences, emotions, biases, nostalgias, memories, impulses, intuitions, opinions, fears, hopes, expectations, and presuppositions about things will be that are rationally rooted in some aspect of how they were in your formation.

I can’t possibly imagine this being a criticism, any more than saying most people form their “accent” based on how the people around them talk when they learn to talk. It is not rocket science.

Memoir of a Dividend Growth investor

I spent the late 1990’s doing financial planning and business management for musical artists and trading tech stocks in my own account. Heavily. I woke up to CNBC every morning. I called my broker a hundred times a day. I bought stocks I had never heard of and made a fortune. I failed to sell stocks I had never heard of and lost a fortune. It was a daily casino that was as much for entertainment as it was perceived financial betterment.

And then I grew up, and by “grow up,” I mean I got married.

I also became an advisor-in-training at Paine Webber. I watched the dotcom implosion, ruin people. It didn’t ruin me because I was young and didn’t yet have the kind of balance sheet that could be “ruined.” But I entered a career in professional investment advice determined to understand mature, lasting, sustainable investment success, overwhelmingly persuaded that whatever I had been doing from 1996-1999 was not it, and whatever most of society had been doing in that era was not it either.

In my book on Dividend Growth investing, I wrote why I believe that growth-of-dividend equity investing was and is the optimal way for long-term investors to access the stock market, whether as “accumulators” or “withdrawers.” I spent years and years studying this, I dedicated my professional life to it, and I am more intellectually convinced of it today than I have ever been.

But experiencing the spectacular flameout of “hopeful” dotcom investing, of “this time it’s different” thinking, of a dramatic divorce from fundamentals, and of the reality of one of the rare “lost decades” in U.S. stock market history helped bring me there. I lived through some of the greatest companies of the late 1990’s lose 85% of their value, and take 15 years to gain it back (or in some cases, 20 years and still counting).

Growth and Value

I am going to save for part 2 next week the really profound discoveries I have to share about the entire subject. In a nutshell, I believe investors are thinking about this all wrong, and there will be a continuation of the present discussion next week I think you will enjoy.

Growth vs. Value – 2020

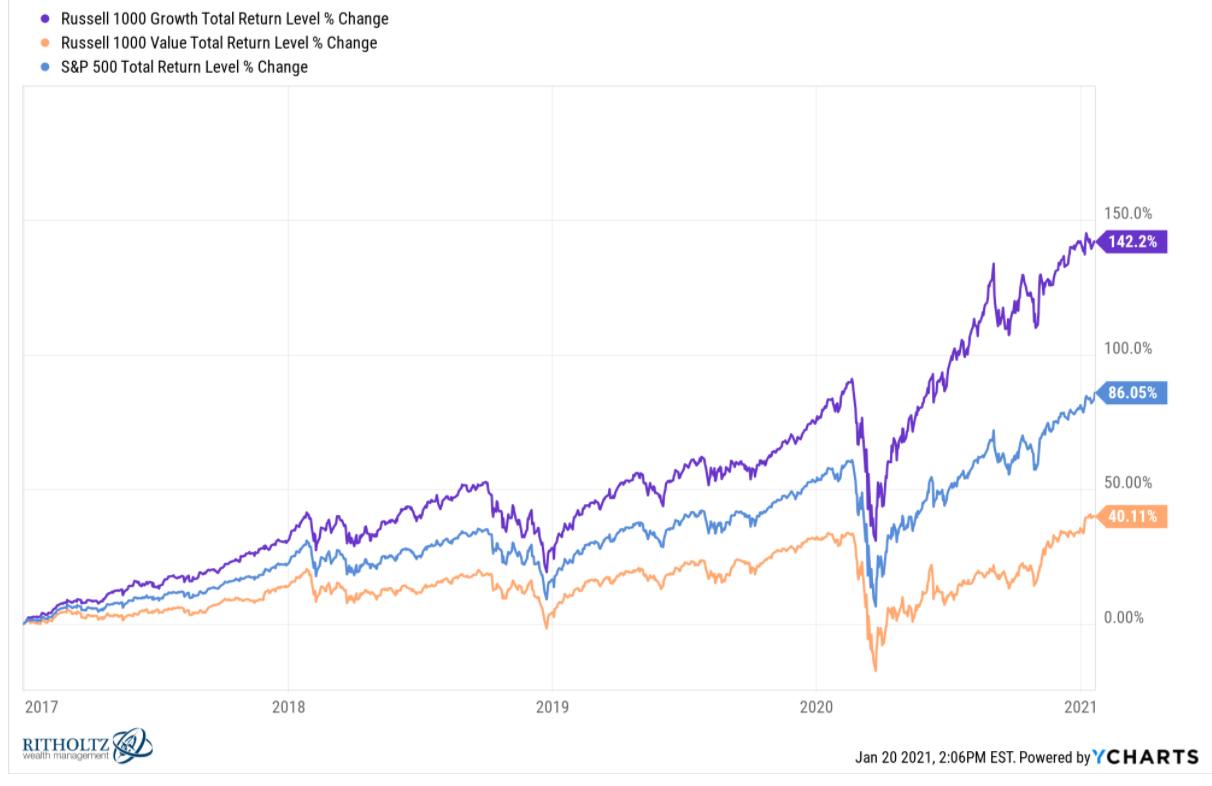

In the immediate period most fresh in investors minds, we can see large-cap growth up 142% over five years, with large-cap value “only” up 40%. A delta-like this, unheard of since the late 1990s, creates a lot of temptation for “recency bias,” of course.

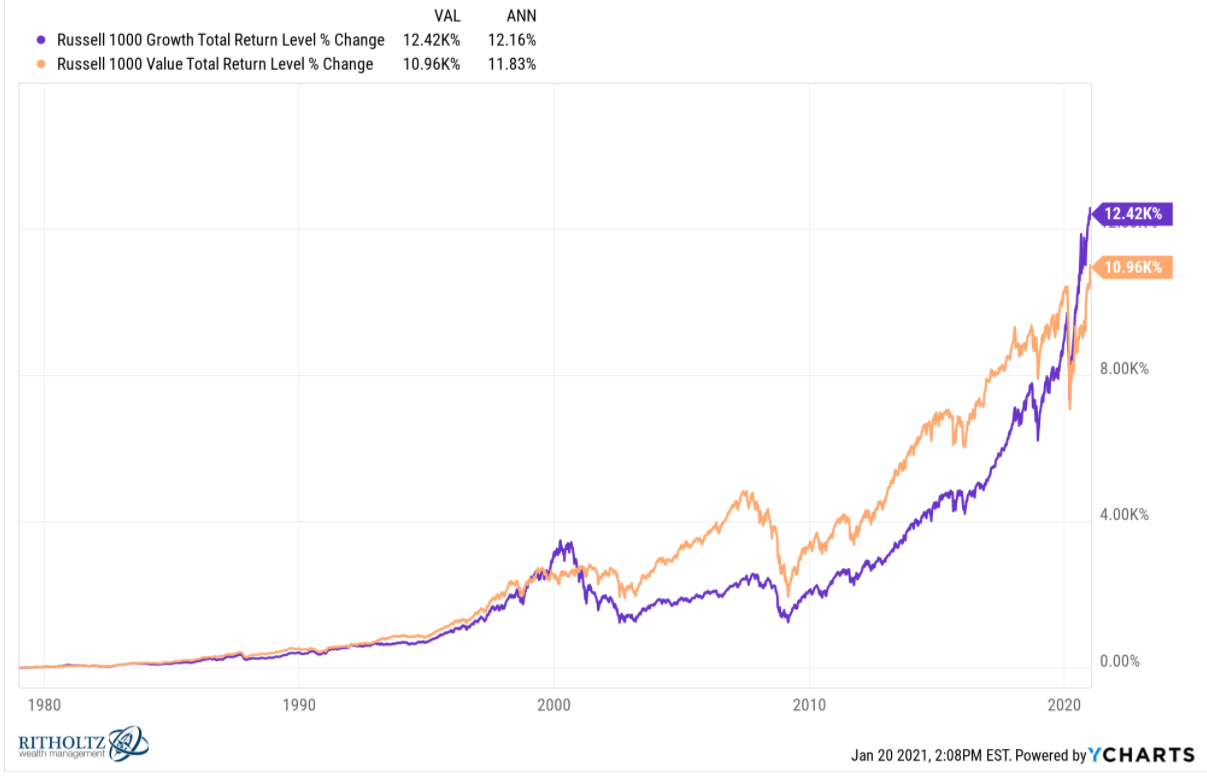

But when we pull the charts back further and look to the entirety of the last forty years, we see that both growth and value have annualized at ~12% per year, with growth peaking out overvalue in the late 1990s as it has 2017-2020, and value outperforming growth 2000-2012, significantly. The back and forth cyclicality of these things is age-old, economically normal, and profoundly important from the vantage point of where we sit now.

Where might dividend stocks fit into this unfolding of reality?

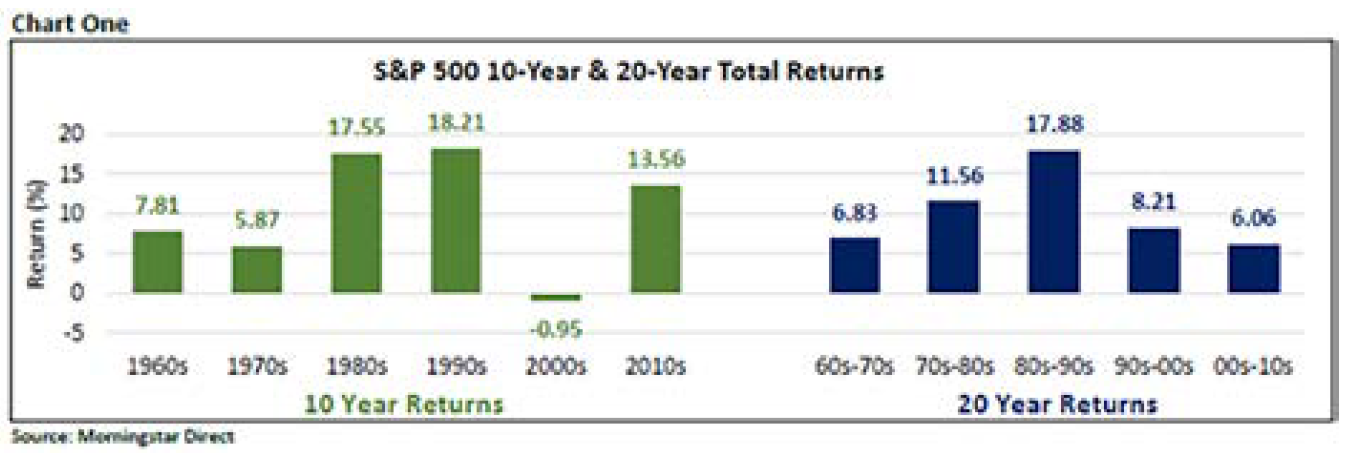

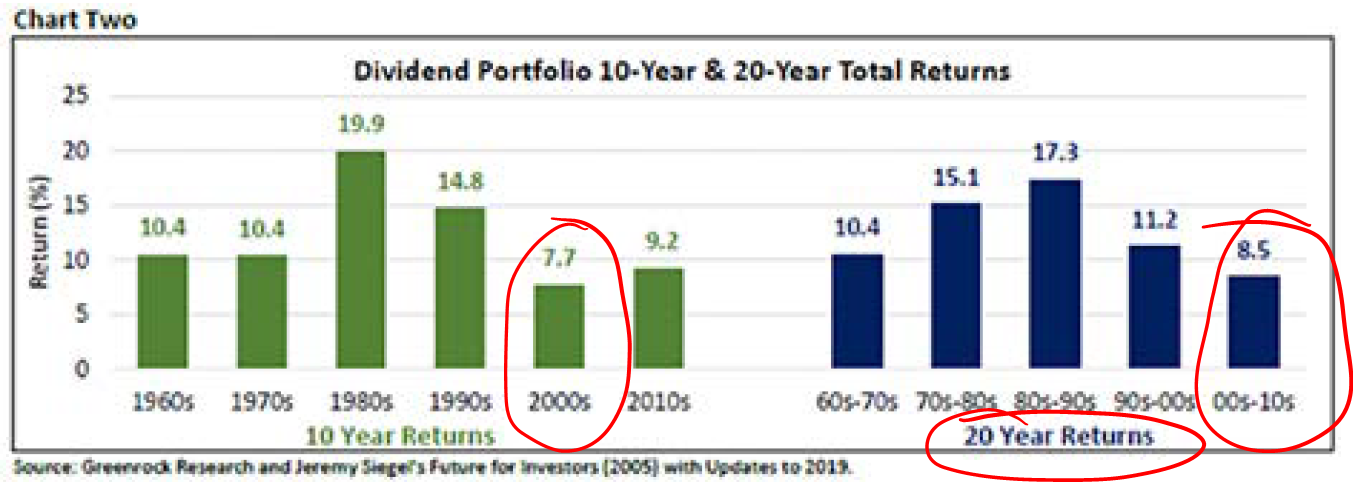

With a H/T to my friend John Mauldin, note the two charts below. The S&P made no money for ten whole years following the tech blow-up, and when you factor in the next huge decade of post-crisis returns is only up 6% per year.

Yet when isolated the top 100 dividend stocks of the index, that -1% per year became almost +8% per year for a decade, and over twenty years, even with the inferior return of the last decade, still trumps the broader market by 250 basis points per year for twenty years.

I should add …

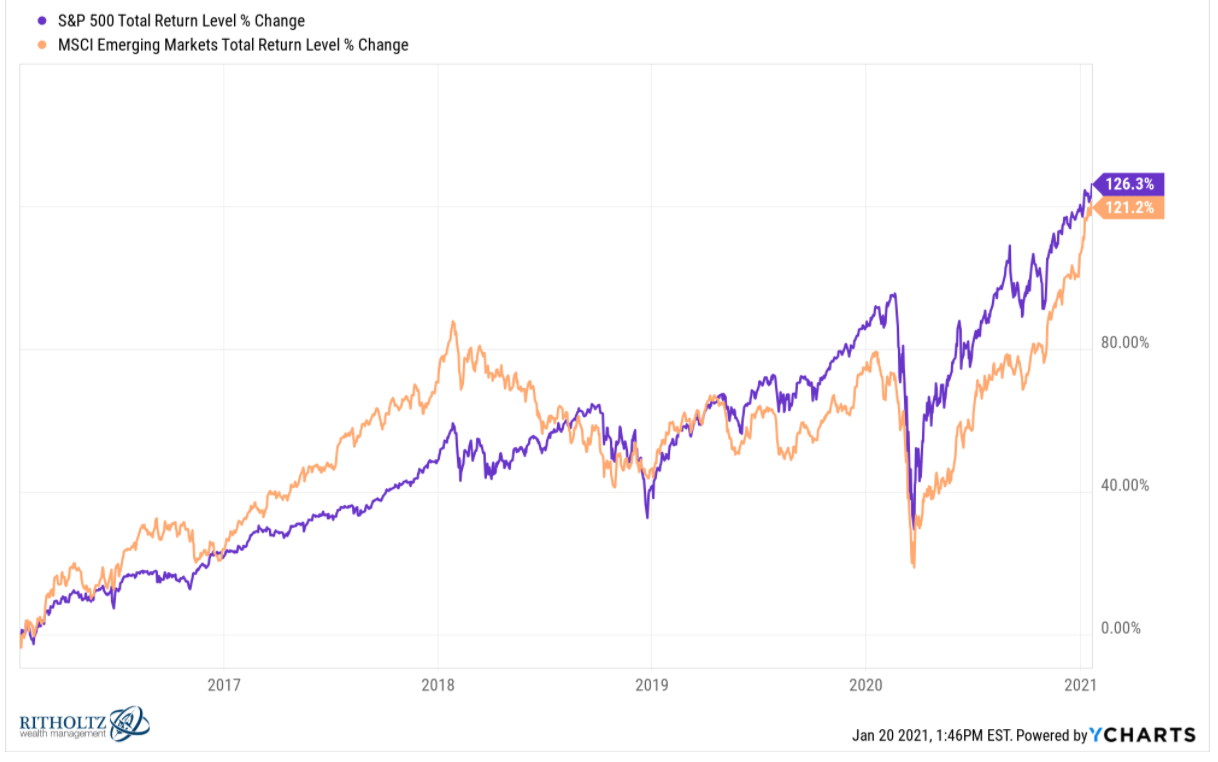

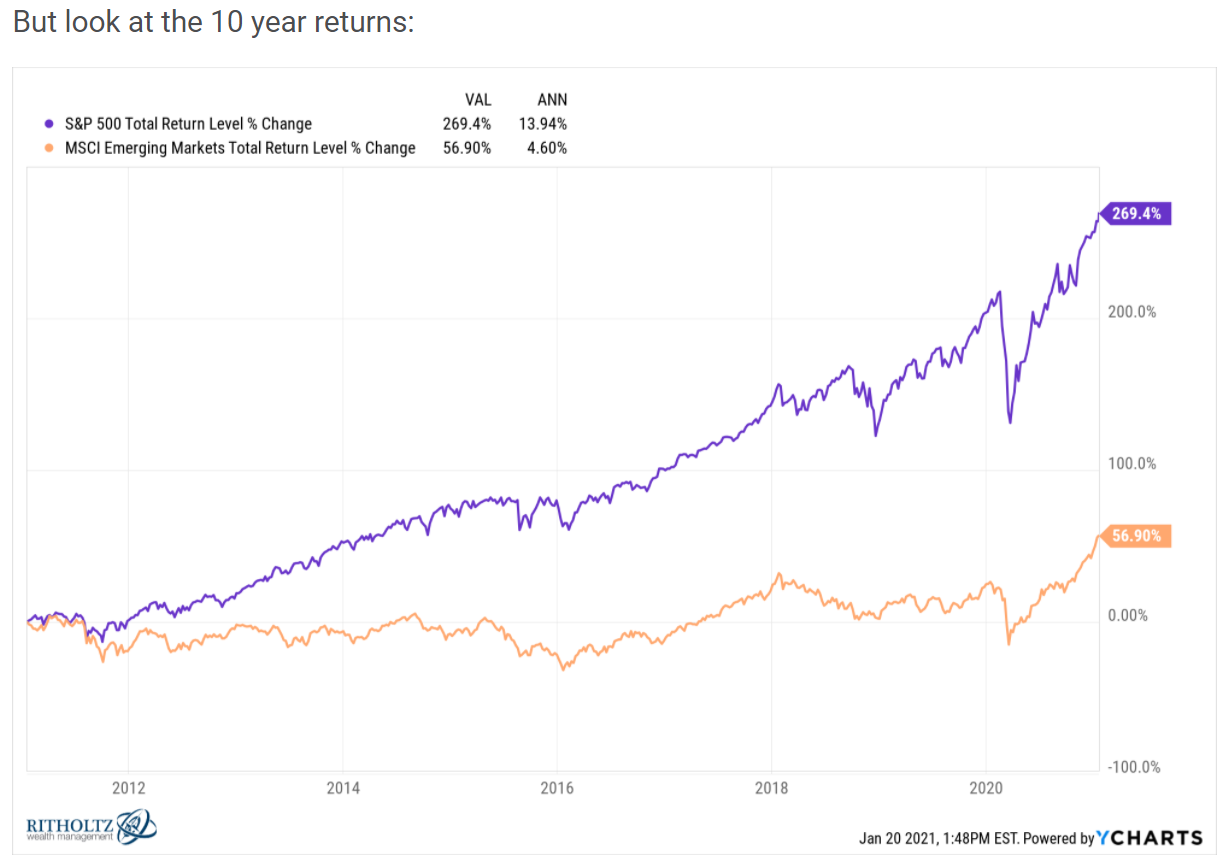

After really under-performing the S&P 500 in 2018, 2019, and much of 2020, it appears that Emerging Markets have now “caught up” to the S&P 500 …

However, just pulling back five additional years shows emerging markets trailing the S&P 500 by nearly 10% per year!

H/T Ben Carlson

Emerging Markets may be one of the few risk assets no one can really call “over-valued” right now. This historical context is important.

A good thing or bad thing?

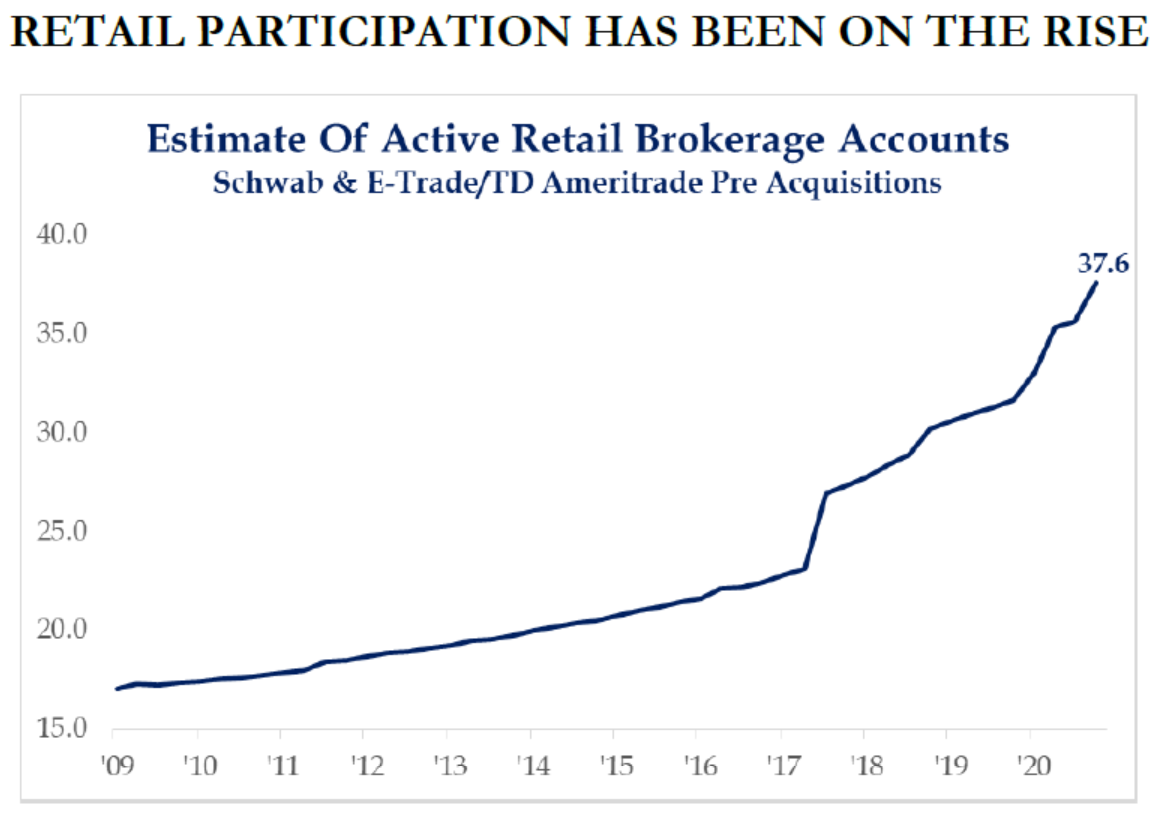

I love capital markets, and more than anything else, I love the compounding of money that makes financial goals possible. More people participating in the financial markets that ought to make compounding possible in a perfect world is a good thing. But one cannot deny from past experience that there is a froth or excess or irrational exuberance that has often been associated with great increase in retail investor participation. What this chart means to the events of this week, or the rise of FAANG valuations, or whatever – is NOT my point. My point here is that there are data points that one should at least know about, whether or not it will alter their outlook and strategy.

*Strategas Research, Charts of the Week, Jan. 22, 2021

Setting the stage for next week

I had a lot more I wanted to share this week and didn’t get it all assimilated the way I wanted. So once again, I am turning this topic into a two-parter. I hope you at least see the context of why this topic is important, where I think we are in the cycle, and what some sensible options are for navigating through it. But if you can wait another week through the thrill of daily news drama, I will unpack more of the present circumstances next week in part 2 …

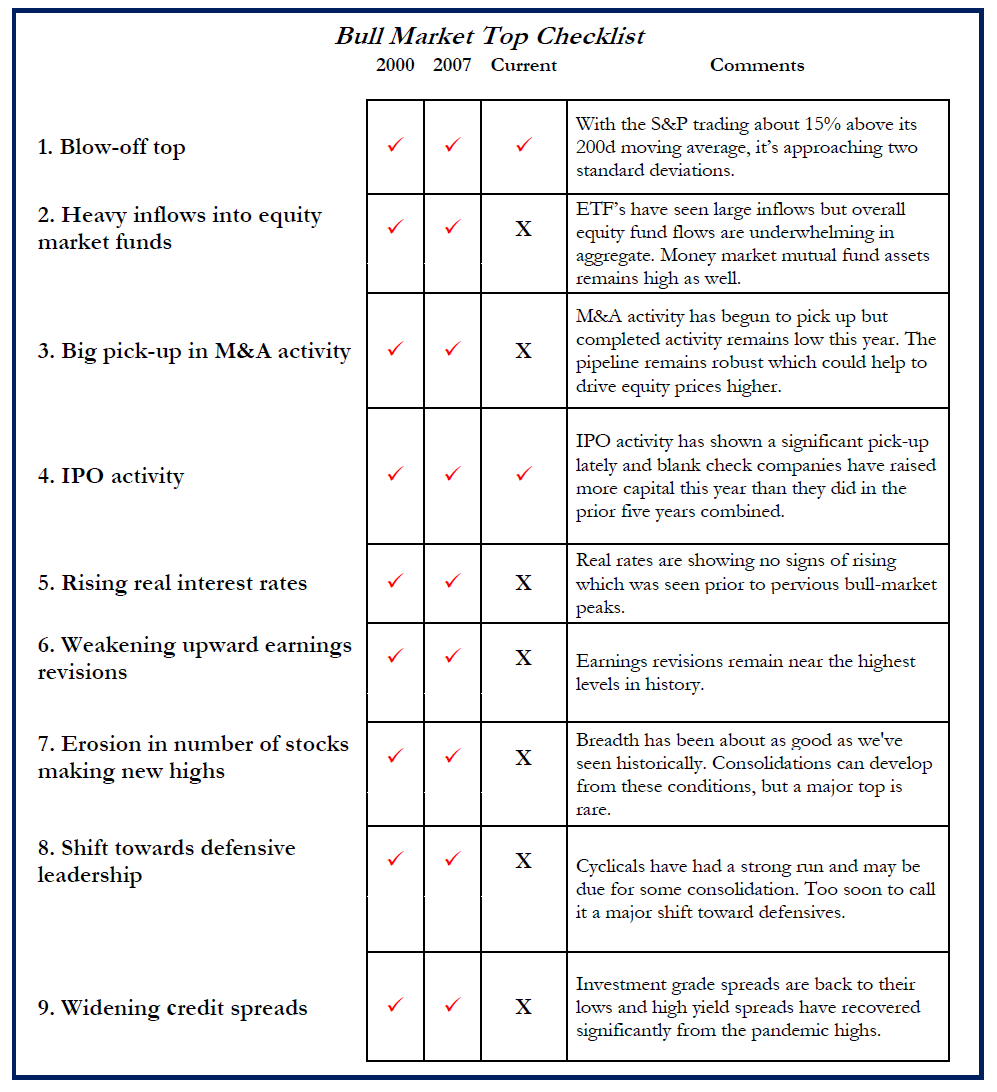

Chart of the Week

Take it as a sign that things are getting bad. Take it as a sign that things still are not that bad. Take it however you want to take it. But this week’s Chart of the Week is shared for historical context and interpretation.

*Strategas Research, Charts of the Week, Jan. 22, 2021

Quote of the Week

“The consensus thinking is generally wrong. If you go with a trend, the momentum always falls apart on you. So I buy companies that are not glamorous and usually out of favor. It’s even better if the whole industry is out of favor.”

~ Carl Icahn

* * *

I spoke with Stuart Varney today about the market activity I allude to in the intro.

I am catching a plane back to California tonight and will be in the California office for the next three weeks. I welcome any questions/comments that the subject of this commentary, or anything else on your mind, generates.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet