Hello TOM Subscribers,

This week we have another guest post from our own, Kenny Molina. Kenny shared his thoughts on behavioral finance a few weeks ago and is back again. This week Kenny will be discussing the F.I.R.E. movement that is sweeping the world of personal finance and he will discuss whether all the potential risks have been accounted for. So sit back, relax, and enjoy the discussion.

– Trevor Cummings

**************************************************************************************************

Retire early, a goal for many to achieve by their mid-to-late fifties but recently there has been a new target proposed by a younger generation. The Financial Independence, Retire Early (F.I.R.E.) movement promotes a questionable goal: retire as soon as possible. Investopedia summarizes the ‘movement’ as:

A program of extreme savings and investment that allows proponents to retire far earlier than traditional budgets and retirement plans would allow. By dedicating up to 70% of income to savings, followers of the FIRE movement may eventually be able to quit their jobs and live solely off small withdrawals from their portfolios.

Traditional retirement planning has primarily focused around two main phases: an accumulation phase during which greater risk (relative to retirement) can be undertaken as time and contributions help weather volatility, followed by the withdrawal phase where income replacement and perseverance of living-standard is the portfolio’s objective. Let’s take the F.I.R.E. movement as a case study of an extreme in the retirement spectrum where the objective is to cash-out ASAP.

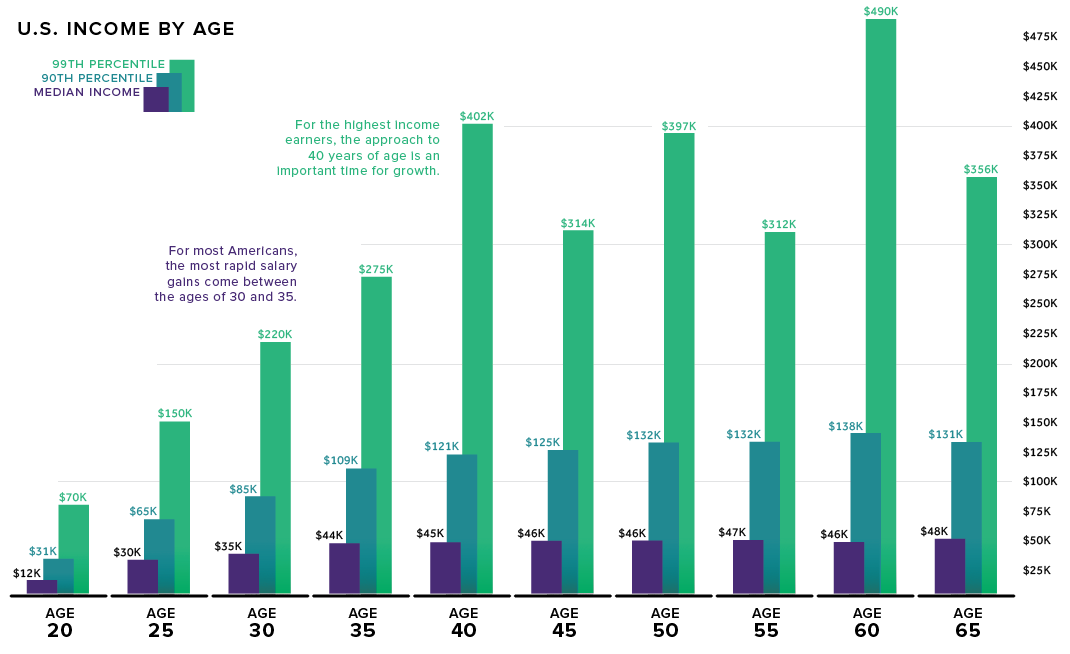

With some participants retiring as early as their late-twenties it becomes clear that well-above-average levels of savings must be undertaken to achieve such an aggressive objective under such an accelerated timeline. Retiring well before any semblance of a full professional trajectory means missing out on years of income at which earnings would be highest. The financial blog Visual Capitalist recently illustrated income earnings from the Bureau of Labor Statistics in a chart that visualizes how earnings tend to peak in our mid-to-late 30’s:

Given that the proponents of the F.I.R.E. movement are foregoing the majority, if not all, of what is traditionally the period during which contributions to a retirement account are at their highest, it begs the question; how?

The basic recipe seems to be; extremely high levels of savings in conjunction with commensurate levels of living expenses until retirement, throughout which one must achieve high single-digit average market returns over an extended period of time to withstand low single-digit withdrawal rates. Tall order. Let’s unpack some of this through a brief review of the minimal hurdles such a portfolio would have to clear over several decades.

Defy the Odds (?)

While results of this approach to retirement are sure to vary, some of the stories that have surfaced regarding such a ‘novel’ approach to a concept that was never designed as an experiment in financial-engineering, are worrisome.

TOM’s recent article covered the truly terrifying monster hiding in the shadows of retirements soft glow, inflation. One fact highlighted summarizes the argument:

FACT: Inflation from 1914-2018 has averaged 3.23%. At this rate, your buying power gets cut in half every 20 years.

Source: minneapolisfed.org

Inflation is the enemy of long-term preservation of purchasing power and investment objectives; just enough and left unchecked will leave an individuals nest egg eroded in value. That fact alone is unnerving enough when planning to retire after 50, now imagine trying to win that fight at 35 or 40. Between inflation, longevity risk (the risk of running out of money during retirement), market volatility, and withdrawal rates a retirement approach such as the F.I.R.E. movement is stacking the odds against its participants and their portfolios.

The last two points take us back to another TOM article regarding sequence-of-returns risk. As the article points out:

Here’s an important truth to remember – your nest egg doesn’t know the difference between negative returns and withdrawals, they both shrink the total.

If these early-retirees forgo the greatest portion of what are the traditional ‘accumulation’ years they are at the whims of market volatility erosion compounded by, what may quickly become unsustainable, withdrawal rates. Even if one were to try and cushion the nest egg with supplemental or passive income they are giving up access to one the most powerful retirement tools we have within our financial systems; tax-advantaged accounts.

Leaving the workforce well before most, if not all, retirement plans will allow tax-sensitive distribution (or even the penalization of such early withdrawals), this approach will effectively minimize the tax-effective implementation of their nest egg throughout the majority of their retirement; give that a moment to sink in.

Life Finds a Way

In addition to the brief list we covered, we should remember; life happens. As the saying goes “Man Plans, and God Laughs”, change is an inevitable part of life. Retiring at these extremes effectively puts one in the position of ‘steering after applying the brakes’. Starting/expanding a family, pursuing a new hobby, or a personal/family emergency are all situations that demand flexibility of not only time but resources. To think one can fully account for the majority of life’s events at 60 and cast-off is a daunting proposition, much more so anywhere near your 30’s (over or under). To live the majority of one’s life minimizing expenses in order to stave off worrisome thoughts sounds like the opposite of retirement.

What this case study shows us is that retirement should not be a finish line to cross, but a journey to embrace. In my opinion, retirement and the adventure that precedes it should be a slow-burn of passion and pursuit. While I can neither promote or criticize the motivations that could lead someone to pursue such a ‘bold’ approach to retirement I would argue that it leaves too much to chance (personally, I subscribe to the planning methodology of ‘hope for the best but plan for the worst’). In the case of these ‘early-retirees’ I could only caution that whether it be a life event or realizing a few years down the line that you dislike the free-lancing that would supplement the portfolio’s income, such an extreme approach accounts little for what a well-planned retirement portfolio emphasizes; life and leisure.