One thing a crisis like we are experiencing can do is drive us to reflect on our investment philosophy and lead us to reaffirm why we believe what we believe.

I assume that most readers of TOM know that I am a dividend growth investor. I am a glutton for dividends and I appreciate the fact that not only are the companies I own continuing to pay a dividend through these trying times, but many of them are also increasing those dividends. For my clients that live off of their portfolio income, this is a godsend.

In addition to being a dividend growth investor, I would also say my investing beliefs very much align with the principles of value investing.

Value investors study the fundamentals (e.g. financial statements) of a company and seek to pay a price that is below what one believes the intrinsic value of the company to be. You might relate this to someone who scours Craigslist for a particular item, looking for the best deal on their desired purchase – the goal is high quality at a great price.

Some of us are just wired this way. We like good deals.

Today we will dive a little deeper into the history of value investing and why I continue to hold tight to my convictions around this style of investing.

Off we go…

A Quick History Lesson…

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 preceded the worst economic downturn in history, The Great Depression. Between the years of 1929 – 1932 the Dow Jones Industrial Average would decline nearly 90% from peak to trough.

Out of the rubble the “Father of Value Investing” arose. It was the year 1934 when a young budding academic by the name of Benjamin Graham published his first book, Security Analysis. Graham would later go on to publish his seminal piece titled, The Intelligent Investor. Perhaps it was these deep Great Depression roots that led Graham to advocate for fundamental sound investing principals as opposed to hopeful speculation.

In 1951 a young and ambitious Warren Buffett graduated from Columbia Business School. Here Buffett met his mentor, none other than Professor Benjamin Graham. Buffett would adopt Graham’s tenets of value investing and carry the baton, going on to be one of the greatest investors of all time.

“Long ago, Ben Graham taught me that ‘Price is what you pay; value is what you get.’ Whether we’re talking about socks or stocks, I like buying quality merchandise when it is marked down.”

– Warren Buffett

Some 40 years later, in 1992 Eugene Fama and Kenneth French, professors at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, published The Fama and French Three-Factor Model. This model provided empirical evidence supporting the long-term premium that value investing earned over a traditional index. In 2013 Fama would go on to win the Nobel Prize for Economics based on this very work.

It Works Most of The Time

With such a deep and rich history, we’d expect value investing to be infallible. Yet, it’s not. There are seasons and cycles in which this style of investing falls out of favor. It is in these times that financial media loves to publish headlines like “The Death of Value Investing.” We saw these headlines during the dot-com bubble of the late 90’s and we see them beginning to surface again today.

In its most simple form, the opposite of value investing would be defined as growth investing or what Benjamin Graham defined as speculation. Speculators are operating under one of two beliefs (1) I believe that someone in the future will pay more for this than I paid today or (2) I believe the forecasted growth of this company will be greater than is currently assumed. I draw your attention to a key difference; value investors are seeking something that is priced today at less than it’s intrinsic value today, while speculators are depending on the future growth being great than today’s expectations. One leans on things knowable today, while the other hinges on accurate forecasting. As nuanced as that may sound, it is a big difference.

So what does the long-term performance of value vs. growth look like?

Source: Volition Financial Network

Source: Volition Financial Network

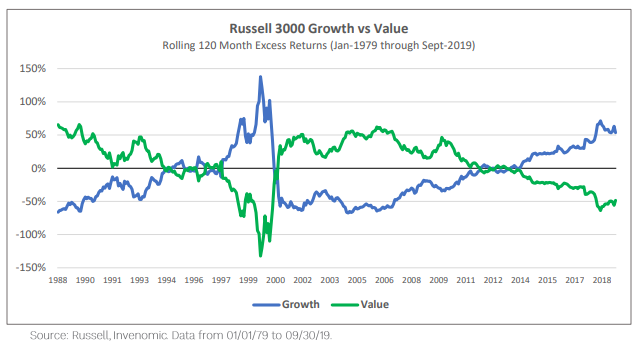

As you will see above, the relative performance of value vs. growth began to shrink leading into the dot-com crash before violently regaining its dominance in the early 2000s. Post Financial Crisis we are yet to see those tables turn again, as we see the relative gap widening to historical peaks.

More Than Charts

Although I believe that the chart above is interesting and provides great context, I don’t lean on this as the foundation for my investment beliefs. Is there a high likelihood that these trends are mean-reverting in nature? I believe so, but this is not my current motivation to be a value investor.

I am a value investor because I like to buy great companies at a good price. Like I said, it’s in my blood, it’s who I am. I don’t think this will change and it’s this alignment that helps me to endure – rain or shine. Does this make me stubborn? I don’t believe so and if it does, at least I am in good company – Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger, Seth Klarman, Joel Greenblatt, etc.

The author of Ecclesiastes says, “What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun.” So whether it was the Nifty 50 of the 60s or the Pets.com of the 90s or the FANG of today, our culture has a long history of worshiping growth companies – so much so that they are willing to pay any price to own them. I, on the other hand, am not. To me, price matters.

Ok, One More Chart …

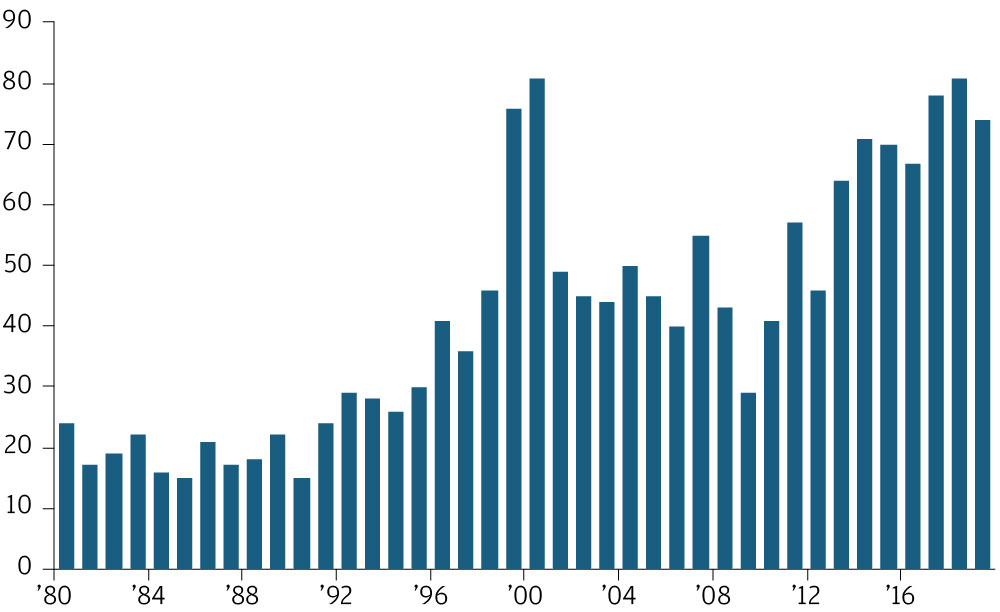

There are endless charts and data that I could provide that has lead me to believe what I believe, but I will spare you. I will close out today’s discussion with one chart that really helps to articulate the type of investments that I prefer to avoid – businesses that don’t make money. I believe this chart also provides a good barometer for what the investor appetite is out there and maybe these peaks are a bellwether for a shift back to fundamental value investing.

US initial public offerings with negative earnings – % of all initial public offerings per calendar year

“In boom times investors are often willing to fund businesses that don’t make any money, but during a recession investors are historically more likely to want to own companies with strong balance sheets that can withstand a downturn. The number of companies listing who don’t make any money has reached levels not seen since the dot com bubble, which may serve as a warning that some young growth stocks could be particularly vulnerable during the next recession” (Source: J.P. Morgan)

With that said, I hope all of you are staying safe and healthy. Again, I know these are trying times and I want to encourage you to reach out with any questions. We value our readers and want to be a resource in any way that we can. You can reach me directly at

Until next week…